Unsustainable Athletic Spending.

Exigency, WVU and You.

Know Your Union.

The last major change to UC’s budget model occurred in 2009/2010, when UC implemented Performance Based Budgeting (PBB) to address UC’s debt load problems and an impending financial crisis. In his February 9, 2024 newsletter, however, Provost Ferme announced the formation of the Next Budget Model Task Force, whose charge is to “produce a model that allows us to have more clarity in how we sustain the university financially moving forward”i. As the task force looks to sustain the university financially, they should carefully examine athletic debt load and the amount of institutional support for athletics.

The last major change to UC’s budget model occurred in 2009/2010, when UC implemented Performance Based Budgeting (PBB) to address UC’s debt load problems and an impending financial crisis. In his February 9, 2024 newsletter, however, Provost Ferme announced the formation of the Next Budget Model Task Force, whose charge is to “produce a model that allows us to have more clarity in how we sustain the university financially moving forward”i. As the task force looks to sustain the university financially, they should carefully examine athletic debt load and the amount of institutional support for athletics.

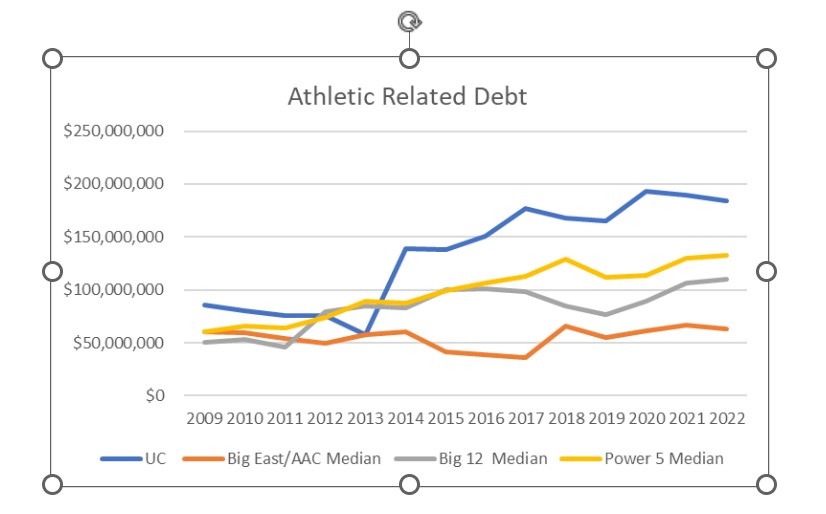

In 2009, UC had $85.9 million in athletic-related debtii. From 2009 to 2013, athletic debt was reduced by $27.9 million to $57.8 million. In 2014, however, athletic debt ballooned by $81 million to $139 million. By 2022, athletic related debt exceeded $184.5 million, which was down by $8.6 million from its all-time high in 2020. To help put these numbers in context, UC’s total academic spending was $ 1.1 billion.

In 2009, UC belonged to the now defunct Big East Conference, and the median athletic related debt load of schools in the conference was 70% of UC’s athletic related debt load. In 2014, UC joined the American Athletic Conference (AAC), and at that time, the AAC’s median athletic related debt load was 43% of UC’s athletic related debt load. By 2022 (the last year of available data), the AAC’s median athletic related debt load had dropped to a mere 34% of UC’s athletic related debt load.

This fall UC joined the Big 12 Conference, which is one of five large conferences that have been granted some self-governing autonomy by the NCAA, and that are often referred to as the “Power 5” conferences. In 2022 both the Big 12 and the Power 5 Conferences’ median schools only carried 60% and 72% of UC’s athletic related debt load. Except for 2012 and 2013, UC’s debt load exceeded the Big East/AAC, the Big 12 and Power 5 conferences median debt load. In summary, for most of the last 15 years, UC has had a larger athletic-related debt load than most of its conference peers.

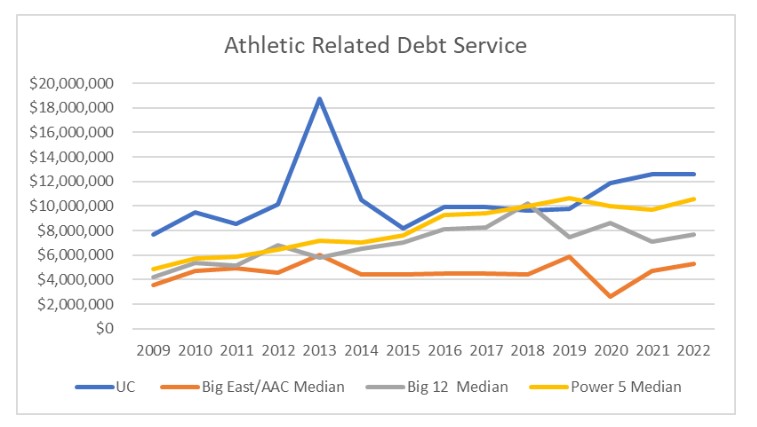

As a natural consequence of a debt load this high, the cost of servicing the debt load also exceeds these groups. In 2022, UC spent $12.6 million on debt service compared to the median schools in the AAC ($5.3 million (42% comparatively), the Big 12 ($7.7 million (61% comparatively)), and the Power 5 ($10.6 million (84% comparatively)). From 2009-2022, except for 2018 and 2019, UC’s debt service expenses exceeded the median schools in the Big East/AAC conference, the Big 12, and the Power 5 conferences.

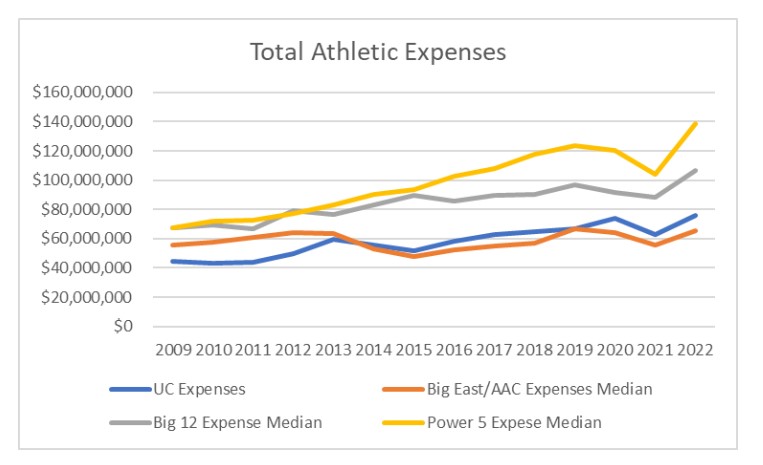

On the surface, UC’s total athletic expenses fare better in comparison than our athletic related debt load. In 2009, the Big East Conference median total athletic expenses were 124% of UC’s, and both the Big 12 and the Autonomy Power 5 Conferences median total athletic expenses were 151% of UC’s total athletic expenses. By 2022, the AAC median total athletic expenses were 87% of UC’s total athletic expenses. The Big 12’s median athletic expenses were now 141% of UC’s, and the Autonomy Power 5 Conference’s median athletic expenses were 183% of UC’s total athletic expenses.

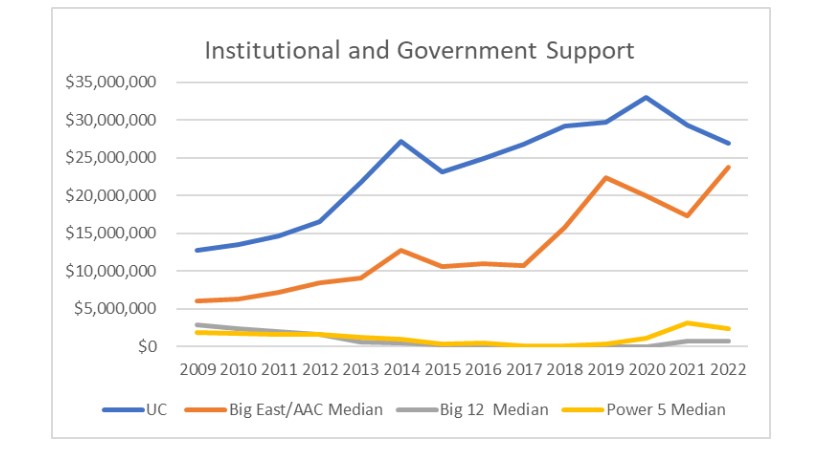

When you examine the source of the “revenues” that cover the athletic expenses, you will find a different story. Institutional and government support—that is, subsidies distinct from money generated by the athletics programs themselves through sales of tickets, apparel, and media rights —is a category of athletics funding counted as a revenue stream by the Knight Commission. From our general funds, UC heavily subsidizes the athletic program. In 2009, institutional and government support was $12.7 million of UC’s athletics revenue compared to the median Big East’s $6.1 million (48% in comparison to UC) in intuitional and government support. The Big 12 and Power 5 conferences’ median levels of institutional support were $2.9 million (23% in comparison to UC) and $1.8 million (14% in comparison to UC) respectively. In 2020, UC hit an all-time high of institutional and government support at $33 million. In comparison, the median AAC institutions provided just 61% of UC’s $33 million. At the same time, the median Big 12 schools provided no institutional or government support and the median Power 5 conference only spent 4% of what UC spent in institutional and government support.

Despite continuously providing significantly more institutional and government support and out-borrowing the median institutions in these conferences, UC’s total athletic expenditures in 2022 were only 71% of the median Big 12 expenditures and 54% the median Autonomy Power 5 conferences total expenditures. To reach the median in athletic expenditures in the Big 12, UC would need to spend an additional $31 million. While UC has a history of spending more than the median in total athletic expenditures of the conferences that it has belonged to, UC can’t afford to do this in the Big 12 without seriously damaging the academic mission of the university. Since 2009, UC has subsidized athletics with $329 million in institutional support and $184 million in athletic debt for a total of $514 million dollars. Athletics is an auxiliary enterprise, which the 2022 UC Budget Book defines auxiliary enterprises as “provide[ing] a service to students, faculty, or staff, and charge a fee directly related to, but not necessarily equal to, the cost of the service. The distinguishing characteristic of an auxiliary enterprise is that it is managed essentially as, and is intended to be, a self-supporting activity.” Although auxiliary enterprises are supposed to be largely self-supporting, these numbers demonstrate, UC athletics is far from self-supporting. As Provost Ferme and the sustainability task force look for ways to help keep UC financially healthy, attention must be paid to athletics and the growing institutional support and the increasing athletic debt load. These trends over the past 13 years are unsustainable if UC is to fulfill its primary mission of academic excellence.

All data in this article came from the NCAA Knight – Newhouse College Athletics Database which can be accessed at https://knightnewhousedata.org/. 2022 is the last year data is available in the database. 2023 data should be available soon.

______________________________________

i March 7, 2024 Provostal Newsletter

ii The Knight Commission defines Athletic Related Debt as “total athletic debt balances owed by the Athletic department.”

iii The Knight Commission includes instruction, research, public service, academic support, student services, institutional support, scholarships and fellowships, and operations and maintenance.”

iv The Knight Commission refers to the Power 5 conferences as the Autonomy 5 conferences.

Exigency, WVU and You

Exigency, WVU and You

March 2024 Chris Campagna

At the beginning of this academic year many faculty were horrified to see the events across the border at WVU—a denuding of the state’s premier university. Of all the many reasons to be unnerved by what we witnessed, what might most account for the depth of our unease was that these actions fit a pattern we’ve seen so many times: in the face of continued withdrawal of state support, university presidents and other administrators—people whose financial acumen we are assured are second to none—mismanage the institution’s finite resources, these same skillful leaders then cut or eliminate “unprofitable” programs and faculty ostensibly to save the establishment from ruin, and the end result is an institution originally founded to serve the public good now to have been re-formed even more in line with market logic and plutocratic priorities.

Even if this story had a familiar shape, though, the notion that the citizens of West Virginia, some of the poorest in the country, did not deserve a fully-fledged land grant university struck many as particularly misguided and, even, heartless. The immensity of President Gordon Gee’s failed construction-intensive plan to attract more students, burdening the school with $800 million dollars in spending that eventually led to a slashing of educational capability on a scale previously unseen in any state flagship institution, was reported by national media as a disturbing singular example of American higher education’s larger ails. Identified as most galling in several accounts was Gee’s decision to fully remove the well-performing World Languages department, leaving students zero opportunity to earn a degree in a foreign language and only four languages—Spanish, Arabic, French, or Chinese—to study at all. After enduring a summer’s worth of widespread media scrutiny and near constant local protest, the administration in September still ended up discontinuing a shocking 28 academic programs with 143 faculty positions—mostly full-time, tenured or tenure-track—eliminated.

The betrayed promise of a truly comprehensive state university for West Virginia’s citizens undoubtedly derives from an erosion of the state’s commitment to a core AAUP principle: shared governance. The AAUP’s 1966 Statement on Government of Colleges and Universities declares that American institutions of higher education should be led jointly by trustees, administration, and faculty, with specific governance responsibilities assigned to each component. Whereas, among other duties, trustees are obliged to “ensure that the institution stays true to its mission” and to “[ensure] that the institution has the financial resources it needs to operate successfully,” and the administration are to “ensure the institution conforms to the policies set forth by the governing board and to sound academic practice” and “provide institutional leadership,” the faculty are responsible for “curriculum, subject matter and methods of instruction, research, faculty status, and those aspects of student life which relate to the educational process.” Obviously, disagreements are inevitable in an arrangement like this. Faculty, for instance, might have thoughts about conducting worthwhile research or “the quality of students’ educational process” that are at odds with trustees’ obligation to maintain the institution’s finances or the administration’s conception of “sound academic practice.” Given the inherent tension in this set-up, each group’s commitment to the general principle of joint responsibility must be paramount. The AAUP’s conception of institutional decision-making imagines an ideal of discussion, debate, and consensus based on a foundation of mutual respect among all governing parties.

Unfortunately (and unsurprisingly), financial pressures have always disrupted that goal. There’s never been a period where American colleges and universities were immune to economic troubles, and, during these times, faculty voices have tended to go unheard by boards and administrators. As early as the 1920s and certainly after The Great Depression the AAUP recognized that claims of institutional hardship placed at risk the ideas advanced in its groundbreaking 1915 document Declaration of Principles on Academic Freedom and Academic Tenure. As recounted in Committee A’s 2013 report The Role of the Faculty in Conditions of Financial Exigency, to address the concern that financial crisis could be used as an opportunity to erode academic freedom and tenure, a 1940 statement jointly issued by the AAUP and the Association of American Colleges indicated that “[t]ermination of a continuous appointment because of financial exigency should be demonstrably bona fide.” In the long stretch between then and now, AAUP investigations of full-time faculty terminations have repeatedly shown that claims of imminent financial crisis are often the product of administrators’ desire to take unilateral action without regard to faculty concerns rather than the result of careful, multifaceted analysis. Over time, then, at the AAUP’s insistence, a formalized role for faculty participation in an institution’s consideration of the need for retrenchment (removal of tenured and tenure-track faculty) due to financial exigency has developed into a norm of American higher education governance. At UC, for example, in the event the university anticipates an “imminent financial crisis which threatens the institution as a whole” Article 28 of our current Collective Bargaining Agreement mandates transparent reporting of financial data, equal opportunity for administration and faculty to present arguments to the trustees, and, if exigency is declared, the creation of a joint administration/faculty Financial Exigency Committee to devise appropriate action to resolve the situation.

Clearly, the spirit of the exigency process is that in an extraordinary circumstance faculty and administration must work together to resolve it. Universities have established these regulations in various forms across the US, though, and ultimately a university’s actions are only determined by the strength of its commitment to shared governance and academic freedom. As noted in Committee A’s 2013 report, institutions have been increasingly eliminating programs without declaring exigency, a practice described by Megan Zahneis of the Chronicle of Higher Education as “near exigency.” In her 2020 piece, Zahneis identified eleven, mostly small private and regional public universities who, in the previous ten years, had used this type of side-step in an attempt to lay off faculty. And this was exactly the move made at WVU in 2023. Institutional bylaws regarding retrenchment there were weak, requiring faculty to be consulted in an exigent situation but allowing for retrenchment without a declaration of exigency. Given the choice to follow the letter of the rule rather than the spirit, Gee’s administration chose the path of least resistance and implemented program and tenured faculty removal without exigency.

Thus, the tone of alarm in the reporting on the WVU situation. If the increasing willingness to abandon AAUP principles at small privates and regional publics has been worrying, the choice for a large state institution such as WVU to do so could mark the start of a significant deterioration in American higher education overall. Michael Nietzel, former president of Missouri State University, points out in Forbes that even a group of schools as traditionally “well-resourced and influential” as the Big Ten now reports a quarter of its members to have “large budget deficits.” And with a reality where “large research universities are not immune to significant financial problems,” Nietzel fears that the actions of WVU could soon be emulated by other large state institutions who find themselves in need of a quick, if substantial, budgetary fix.

Here at UC, Val Ferme reported in the February 9 “Provost Update” to faculty and staff that we are in a different position, with at least a two-year period of predicted financial stability that should allow for us to prepare now for anticipated coming challenges, taking “preventive rather than reactive action” with “thoughtful rather than hurried analyses.” That sounds good; we don’t need to be worried that exigency would be declared here any time soon, and we all—administration, faculty, and trustees–have time collectively to work on solutions to potential economic troubles. It’s the Provost’s next paragraph, however, where we should feel some concern, when he invites faculty to be “supportive” of UC’s current institutional review by being “engaged in the process as allies who want to construct a better future.” That language sounds less in the spirit of shared governance and more a prompt to keep quiet unless one’s vision for the university aligns with the administration’s (perhaps not coincidentally, Provost Ferme announced the convening of a Presidential committee on “civility” in this same message). This is the type of perspective that opens space for administrative moves justified by “near exigency,” an attitude described by Michael Berube in his 2020 reflection on the Committee A report where “decisions with serious implications for the curriculum are construed not in curricular or intellectual terms but rather as budgetary matters over which the faculty should have no jurisdiction.” Provost Ferme’s belief that we’re all in this together is correct—we are, and we all have our role to play in planning a future for our institution that may not look exactly like its present.

As always, then, faculty attention and engagement are the proper response if we want to live up to the standards the AAUP espouses and if we truly believe in serving the public good. UC’s capital investments and continued administrative bloat may not have yet caused the kind of catastrophic damage to the budget as those at WVU did, but UC—as many universities—has followed that general playbook closely enough that our faculty still need to be wary. And as much as we should be grateful that Provost Ferme thinks to include faculty in assessing UC’s future, many in the Ohio state legislature want to remove one of the most powerful means by which we able to influence university governance, our collective bargaining rights. The practice of exigency before retrenchment follows directly from the principles of academic freedom and shared governance which, themselves, follow from the belief that higher education is a special, community-focused endeavor with a different mission than the corporation down the street. The WVU fiasco provides further evidence that faculty will need to step up to the challenge of defending what we see as uniquely important and valuable about our profession if we don’t want this mission changed. The collective energy and effort we bring to our local, state, and national AAUP organization in the coming years will hopefully be the deciding factor.

On Tuesday, March 26th, the Chapter held a training with National AAUP organizing expert David Kociemba. Much fun was had, as members practiced role-playing, shared stories of their own union commitments, and got to know each other better. The Chapter will be conducting a Membership Blitz between now and the end of the semester, as we celebrate 50 years of collective bargaining, and as we gear up for next year’s contract negotiations.

On Tuesday, March 26th, the Chapter held a training with National AAUP organizing expert David Kociemba. Much fun was had, as members practiced role-playing, shared stories of their own union commitments, and got to know each other better. The Chapter will be conducting a Membership Blitz between now and the end of the semester, as we celebrate 50 years of collective bargaining, and as we gear up for next year’s contract negotiations.

You can find out more about your Chapter and your CBA here, and you can easily join as a full member here. Expect to see folks dropping by or knocking on your office doors in the coming weeks. Remember, we are stronger together.