Click here to read the President’s Corner.

Click here to read The More Things Change …: UC Instructional Spending Still Lagging, Despite Increased Enrollment

President’s Corner

As faculty are aware, the UC Board of Trustees launched the search for former President Santa Ono’s replacement in June of this year. Rob Richardson, Board President and chair of the Presidential Search Committee, promised that the process would be “open, transparent, and collaborative.” Unfortunately, it has been neither open, nor transparent, nor collaborative. To the contrary, the process has been shrouded in secrecy, lacking comprehensive faculty and student input, and in violation of well-established best academic practices.

To add to the consternation caused by this secretive search, The Cincinnati Enquirer recently reported that former Procter & Gamble CEO and the current Secretary of Veterans Affairs Robert McDonald has emerged as a leading candidate. The leak of information poses two problems for the faculty. Since we have no other information to work with, we must assume that Secretary McDonald is the only candidate being seriously considered. While that may, or may not, be a fair assessment of the situation, it would be unwise for faculty remain silent and not offer our opinions regarding the candidate. Second, hiring a president without academic credentials is a serious concern for those of us who work in higher education. When the University of Iowa decided it would abandon the accepted standards of shared governance and appointed Bruce Harreld, former IBM senior vice president, as president it was met with fierce criticism from the faculty and students. Harreld, one of the four finalists, lacked the qualifications and experience found in the other three candidates and yet the Board of Regents offered him the position due to his success in the private sector. Faculty questioned not only his academic background but also the fact that he lacks any experience in public service. Eventually, the University of Iowa found itself on the American Association of University Professor’s list of sanctioned institutions for “substantial non-compliance with standards of academic government”.

While it is possible that an unconventional candidate could be an appropriate fit for UC, it is imperative that the process be truly open, transparent, and collaborative ensuring that all constituents at UC have a voice at the table. It’s the right thing to do and will ensure that the right candidate is chosen for the job.

Secretary McDonald, if he is truly a candidate, and the other candidates should be made public and come to UC for public interviews with students, faculty, and other stakeholders. This would provide much needed confidence in the hiring process and a solid foundation for the new president to begin his tenure at UC. The process would also benefit the prospective candidates, providing them with the knowledge and confidence that UC is truly the best match for their skillset.

Regarding the search process itself, as the Chapter previously communicated, both the National AAUP and the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges (AGB), a national association of university boards of trustees (of which the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees is a member), have issued policy statements opposing closed-door, secret searches for university presidents.

In 1966, a joint Statement on the Government of Colleges and Universities was developed by the AAUP, the American Council on Education, and the Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges. Of utmost importance, the joint statement states:

“Joint effort of a most critical kind must be taken when an institution chooses a new president. The selection of a chief administrative officer should follow upon a cooperative search by the governing board and the faculty, taking into consideration the opinions of others who are appropriately interested. The president should be equally qualified to serve both as the executive officer of the governing board and as the chief academic officer of the institution and the faculty. The president’s dual role requires an ability to interpret to board and faculty the educational views and concepts of institutional government of the other. The president should have the confidence of the board and the faculty.”

In November 2015, the National AAUP reaffirmed its policy on secret presidential searches, stating:

“…decisions to forgo public campus visits and public forums by finalists violate longstanding principles of shared governance. Shared governance helps ensure that universities and colleges serve the public interest. Serving this interest is why we have public universities and colleges and why we grant special tax status to nonprofit private universities and colleges.”

The statement concludes:

“The AAUP thus calls upon colleges and universities to resist calls for closed, secretive searches and reaffirm their commitment to transparency and active faculty engagement in the hiring of higher administrative officers. Faculty members should demand that their institutions observe established norms of shared governance by involving faculty representatives in all stages of the search process and by providing the entire faculty and other members of the campus community the opportunity to meet with search finalists in public on campus.”

The full AAUP statement can be read here.

Thus far the UC presidential search has not been conducted according to either the spirit or letter of the shared governance principles in the AAUP-UC Collective Bargaining Agreement, National AAUP policies, or policy statements of the AGB, of which UC’s Board of Trustees is a member. The hope and expectation is that UC will immediately enter a more open phase of this vital search.

Ron Jones

President, AAUP-UC Chapter

The More Things Change . . . : UC Instructional Spending Still Lagging, Despite Increased Enrollment

When the UC Administration spends large sums of money on its building projects or on coaches’ salaries, these expenditures make the headlines. Most recently, in the wake of the resignation of UC football coach Tommy Tuberville, the Cincinnati Enquirer reported that the “financial terms” of his resignation are “being worked out.” (“UC Confirms Tuberville Is Leaving,” Groeschen, T., 4 Dec. 2015, Available online here). Given that only two months ago, Tuberville signed an oddly-timed contract extension with the UC Administration that more than doubled the payout for Tuberville if UC were to let him go before January 31, 2017 (from the original $1 million to $2.4 million), it is fair to speculate that these “financial terms” will be generous to Tuberville.

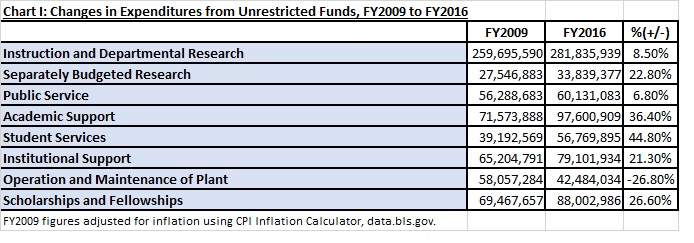

The UC Administration’s casual largesse with Tuberville stands in sharp contrast with its approach to spending on academics. Over the past several years, we have examined the UC Administration’s expenditures in the face of a dramatic rise in student enrollment (from 29,593 FTEs in Fall 2008 to 34,421 in Fall 2015, a 16.6% jump). As student enrollment rose, spending on Instruction was far outpaced by increases in other sectors, particularly Academic Support (academic administration, including college offices) and Institutional Support (finance administration, the President’s office, Enrollment Management, etc.), as indicated in Chart I. See also, e.g., ”Education on the Cheap,” Works, Vol. 22, No. 3, 30 Mar. 2015).

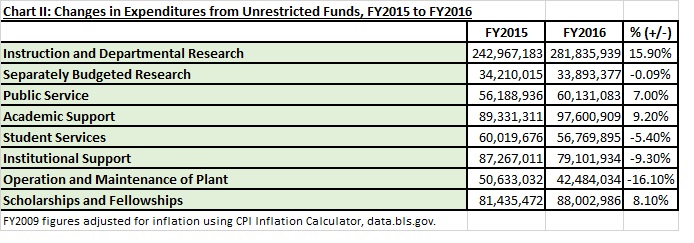

Given years of relatively stagnant spending on Instruction, the University’s Annual Fund Accounting Schedules for the 2015-2016 fiscal year (FY2016), released in November, at first glance bring welcome news of a much-needed reinvestment in Instruction, as indicated in Chart II:

The nearly $39 million dollar one-year jump in spending on Instruction is eyebrow-raising, to say the least. Unfortunately, a deeper dive into the FY16 Schedules shows that this number does not represent an across-the-board infusion of funds into the colleges. Rather, $28 million of this increase is attributable to an increase in spending in one college: the College of Medicine. Given the unique complexities of budgeting and finance at the College of Medicine, it is difficult to say with any certainty how the $28 million increase came about, though it merits further investigation.

As for the remaining $11 million in increased Instructional funding, the following items are notable:

- $3.2 million is attributable to the College of Education, Criminal Justice and Human Services (CECH).

- $2.8 million was allocated to the College of Business. Notably, of the $25.7 million spent on Instruction in the College of Business, $2.17 million was spent by the Dean’s Office. Although most Dean’s Offices (except in the College of Law) account for a share of Instructional spending in their colleges, in most cases the proportion is 1-2%. In Business, over 8% of Instructional spending was attributable to the Dean’s Office in FY2016, a massive increase over its 1% share in FY2009.

- $1.7 million is attributable to the College of Engineering and Applied Science (CEAS).

Accordingly, while a $39 million boost in funding at first seems very impressive, a closer look shows that more than two-thirds of that is attributable to one college, while only three other colleges saw increases of over $1 million.

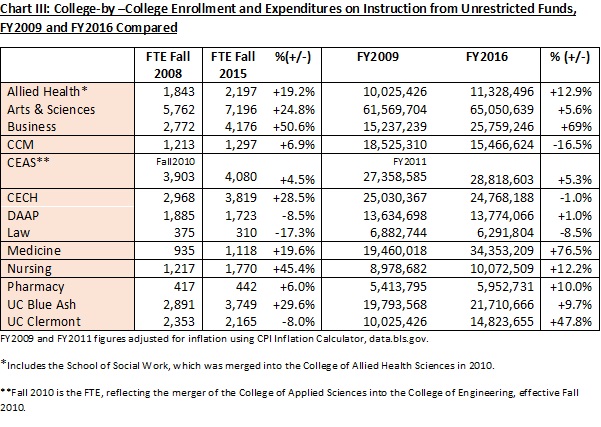

The incongruity between increases in Instructional funding and FTEs among the colleges is illustrated in Chart III:

The data in Chart III defies generalization, as there is no direct correlation between increases and decreases in FTEs and Instructional funding, and the proportions thereof:

- In Allied Health, Arts & Sciences, CCM, CECH, Nursing, and UC Blue Ash, the percentage increases in FTEs exceeded the percentage increase in instructional funding. This discontinuity is most evident in A&S and in UC Blue Ash. CECH actually saw a slight decrease in Instructional funding over this time.

- In Business, Pharmacy, and CEAS, Instructional funding actually increased by a larger proportion than did FTEs. (This occurred at Medicine, too, but given its unique and complex funding structure, it is difficult to say exactly how this discontinuity arose. In other words, the relationship between Administration priority-setting and the financial arrangements at Medicine is more opaque.)

- In two colleges, FTEs decreased while funding actually increased over the same time period: DAAP and UC Clermont.

- At DAAP, FTEs had actually peaked at 1,979 in Fall 2010, dropping gradually to its present level. It is unclear at this point what factors are at play in bringing about this decrease, but it is safe to say that future growth will depend on, at minimum, maintaining the strength of DAAP’s programs.

- At UC Clermont, FTEs skyrocketed to 2,829 in Fall 2011, dropping below its Fall 2008 levels beginning only in Fall 2014. UC Clermont’s significant fluctuations in enrollment are attributable in part to the impacts of the Great Recession (spurring enrollment) and the improving economy (with greater employment prospects reducing the impetus among some for higher education). While the reduction in FTEs undoubtedly is putting pressure on UC Clermont’s budget, we hope that the UC Administration will extend the same patience and forbearance with UC Clermont as it has to the Athletics program, which has lost money for well over a decade, with little prospect for profitability in the near (or even distant) future.

Conclusion

The University’s financial schedules can only show the results of the Administration’s budgetary decision making process. Only by juxtaposing those results with other data—such as FTE enrollments—can we begin to determine whether the numbers “add up.” Such an analysis often leads to more questions, such as: “Why did Business’s Instructional funding increase by an even faster proportion than its FTEs, while A&S’s Instructional funding fell dramatically behind?” “Is it reasonable to expect a college such as A&S to teach nearly 25% more FTEs with less than a 6% increase in its Instructional funding?” “How can CCM be expected to teach nearly 7% more FTEs with 16% less funding?” And so on. Although the University has utilized the Performance Based Budgeting process for 8 years now, these numbers, at least, show little relationship between a college’s “performance” (measured in FTEs) and its Instructional “budget,” at least. The complex formulas in the PBB process may carry an internal logic to some, but the results they yield, as indicated on Chart III, appear in some cases to be at best illogical, and at worst detrimentally unfair.

—Stephanie Spanja, J.D.

Director of Research, UC Chapter AAUP