Click here to view “War on Higher Ed”

Click here to view “High Hopes, High Stakes”

President’s Corner

President’s Corner

As a first generation college student there was, in my family, a belief that higher education was a good thing. Like many blue collar families, education was the vehicle to a better life. The biggest problem we faced was that more people needed access to it.

Fast forward to 2017 and this is no longer the case. Higher education is now a wedge issue, a tool to divide people and sow distrust, fear, and resentment.

Look at the U.S. Congress’ proposed budget and its impact on higher education. First, it proposes eliminating the tax exemption on tuition waivers. This means that a student’s tuition reduction in exchange for teaching, research, or other work for the university becomes taxable. In other words, a $40,000 tuition waiver would be counted as income to be taxed. Further, this “income” would push many graduate students into a higher and more heavily taxed income tax bracket. The result for hundreds of thousands of graduate student would be thousands of dollars of extra tax debt per year. This makes it dramatically more difficult to get a PhD or other advanced degree in the United States.

(Note that this bill, as currently written, would not impact UC faculty tuition remission since work is not required for the faculty or their dependents to receive that benefit. Nevertheless, if this bill passes tuition remission benefits such as those guaranteed by the Collective Bargaining Agreement could be the next target.)

The situation gets worse for graduate and undergraduate students upon graduation. Faced with the mounting student-debt crisis does Congress do anything to combat it? Quite the opposite. They propose eliminating the current tax deduction on student loans (up to $2,500) per year. This will lead to more debt and make higher education less attractive.

The proposed budget also provides an excise tax on some of the largest, wealthiest private school endowments. An initial reaction might be little sympathy for these heavily-endowed private institutions, but the question becomes if they are being targeted today, which other endowments or higher-ed support structures will be next?

Simultaneously with the threats from Washington, or perhaps because of it, faculty are being harassed by individuals and groups that view free speech and academic freedom as threats. This includes the Professor Watchlist that targets faculty that “advance leftist propaganda in the classroom.”

There is a very real war on higher education. These attacks on higher education will intensify and the situation is likely to get worse before it gets better. There is no an easy or universal solution here. We must continue to look for ways to be a positive influence in our community. Here are a few suggestions. Take the time to build relationships with your students and talk to them about these critical issues. Put your name on the Faculty Watchlist in support of your colleagues that are being targeted If you are not a member, join the AAUP. Perhaps it is some solace to remember that the AAUP has been fighting challenges to free speech, academic freedom, and other threats to higher education since its inception. The road will be long, the battles many and sometimes brutal, but we will endure and prevail.

High Hopes, High Stakes: Division 1-FBS Intercollegiate Athletics at UC and hte Never-ending Quest for the Big Payday

High Hopes, High Stakes: Division 1-FBS Intercollegiate Athletics at UC and hte Never-ending Quest for the Big Payday

Part II: UC Antes Up

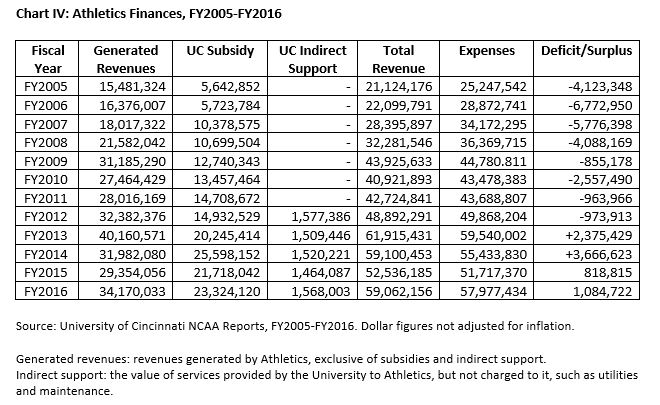

When UC Athletics started competing in the Big East in Fall 2005, it was already over $99,000,000 in debt, and it ran an operating deficit of nearly $7,000,000 for FY06, even with a subsidy of $5.7 million from UC.[i] Ten years later, in FY2016, UC Athletics was over $150,000,000 in debt, and while it technically showed a “surplus” of a little over $1 million, this was only because UC’s subsidy had quadrupled to $23.7 million, fueled in part by several major building projects.[ii] In fact, from FY06 to FY16, the UC Administration subsidized UC Athletics by over $170 million.[iii]

It wasn’t supposed to happen like this. Throughout the past decade and beyond, UC Administration issued a series of optimistic predictions that, in just a few years, UC Athletics would begin to break even—or at least not require more than the subsidy it had received in the early 2000s. With each year, this goal appeared to recede further into the horizon. Now, where once the distressed state of UC Athletics’ finances was a topic of extended discussion and concern at meetings of the Board of Trustees (“BOT”), there is barely mention of this issue anymore, much less identification of it as a problem to be addressed. The price of admission to a major conference—the Big East—and the price of seeking future admission to a Power Five conference, in the form of “investments” in facilities and lavish compensation for coaches—has now become an ongoing cost of doing business, accepted seemingly without question by UC Administration and the BOT.

Why is this so? The willingness to spend more and more on UC Athletics likely stems in part from the continued belief in the prevalent myths about intercollegiate athletics (see Part I). These misconceptions, and the failure to undertake a cost-benefit analysis based on actual data, as opposed to emotion, are at the root of many decisions that UC Administration and the BOT have made which have brought the University to this point. The following is a look at how UC Athletics landed where it is today—heavily subsidized and deeply in debt.

2002: UC Starts Spending Big to Hit the Big Time

At its November 36, 2002 meeting, the BOT approved the construction of Varsity Village, at a cost of $109 million.[iv] The Varsity Village project included, among other things, “the construction of an Athletics Center, outdoor fields and courts, a below grade in-fill garage, the Student Health Services project, the University Multipurpose Club project.”[v] UC Athletics was expected to cover $41 million, or just over a third, of the total cost through donations, but only had $4 million on hand during the construction process.[vi] So, the BOT allowed the University to borrow to cover the unfunded portion of UC Athletics’ obligation, to “bridge the receipt of the remaining gifts.”[vii]

Interestingly, UC was not in a strong financial position when the BOT allowed it to add over $100 million to its debt load to fund the Varsity Village project. Just one year prior, in November 2001, the BOT had called a special meeting to address “some serious financial problems,” namely, an $11 million shortfall due to mid-year budget cuts from the state; the BOT addressed this problem in part with a 2% mid-year tuition increase.[viii] In fact, the Ohio State Share of Instruction (“SSI”) had been dropping for years, with no increases on the horizon, as the BOT publicly acknowledged in a November 5, 2001 special meeting at which it approved an emergency mid-year tuition increase to address an $11 million shortfall in state funding.[ix]

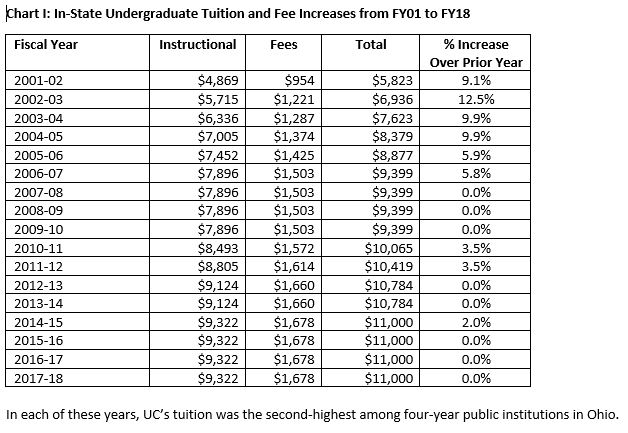

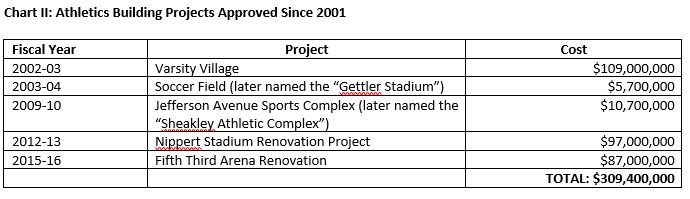

In fact, the BOT raised tuition significantly—by 9.1% for 2001-02, and again by 12.5% for 2002-03—prior to approving the Varsity Village project, which is itself extraordinary. (See Chart I) Even more stunning was the lack of any public deliberation at that meeting as to whether it would be wise for UC to take on such a huge debt burden for Varsity Village, given the plunge in state funding and the recent large tuition hikes. Similarly lacking was a discussion of whether UC Athletics realistically could be expected to raise over $40 million in donations to help fund the project, given that it was projected to receive the same $4.1 million in donations in FY03 as it had in the previous year—and even with those donations, it required approximately $4.5 million in subsidies to balance its budget.[x] Varsity Village was just the first in a series of major UC Athletics building projects undertaken since 2002, at a combined total cost of over $300 million. (See Chart II)

2003–2006: UC Enters the Big East

The Varsity Village project was in part an effort to enhance UC’s attractiveness to a major conference suitor. This effort bore fruit in November 2003, when UC announced that it had accepted an invitation to leave Conference USA and join the Big East, a major conference which would afford the UC football team to compete in Division I-FBS (then “Division I-A: “Championship Series”).[xi]

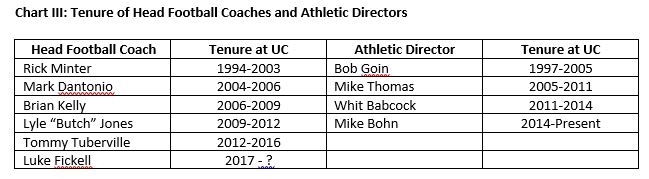

The period from 2003–2006 is notable not only for the firing of men’s basketball coach Bob Huggins in August 2005[xii] and his replacement by Mick Cronin,[xiii] but also for the beginning of an era frequent turnover of football coaches and Athletic Directors at UC. In January 2004, Mark Dantonio became the first of five new head football coaches who would be hired at UC between 2004 and 2016. Two years later, in 2006, Mike Thomas replaced Bob Goin as Athletic Director; he would be succeeded by three Athletic Directors (“ADs”) in less than ten years. (See Chart III)

In his remarks to the BOT at its June 27, 2006 meeting, AD Mike Thomas reflected the prevailing sunny outlook among UC leadership when he expressed high hopes for UC Athletics in the coming years, saying “[W]e are going from good to great. We want to be the DAAP and CCM of college athletics.”[xiv] Thomas commented that the recently-dedicated Richard E. Lindner Varsity Village was a “difference maker” which put UC “ahead of the Big East facilities curve and is already paying dividends, especially in the area of recruiting.”[xv] In a nod to one of the rationales for investment in Division I intercollegiate athletics, Thomas stated: “We cannot underestimate athletics’ role in the marketing of this institution and [we] recognize that athletic success is crucial to our ongoing efforts of extending our boundaries beyond the institutional draw of Southern Ohio.”[xvi]

Optimism does not pay the bills, however. Year by year, state funding continued to comprise a shrinking portion of UC’s overall revenues, dropping from 25% in FY03 to 21% in FY06.[xvii] During this time, tuition continued to rise, going up by 5.9% in FY06, the first year of UC’s membership in the Big East. (See Chart I) While the UC Athletics subsidy held roughly steady at $5.7 million, FY06 would be the last year that it would remain below $10 million.

2007–2009: Winning, But Not Breaking Even

At the end of 2006, Brian Kelly became the new head football coach.[xviii] The UC football team made several bowl appearances both immediately before and during Kelly’s tenure, including the International Bowl and the Papa John’s Bowl in 2007 (both of which UC won), the Orange Bowl in 2009, and the Sugar Bowl in 2010.[xix]

Although the UC football team was experiencing success on the field, UC Athletics’ overall financial situation was not improving. Revenues failed to keep pace with expenses, the UC Athletics subsidy more than doubled from FY06 to FY09, when it topped $12 million, and UC Athletics continued to run millions in deficits. (See Chart IV) Minutes of the BOT from that era reflect an increasing sensitivity—and defensiveness—about this issue. For example, at the June 24, 2008 BOT meeting, then-Senior Vice President of Administration and Finance Monica Rimai noted that “one of the huge challenges Athletics will always have is much of their economic fates are dependent upon their win/loss record.”[xx] Continuing, Rimai asserted that “Athletics is as much a part of the student experience as MainStreet, as the Rec Center, as Enrollment Services, as any of the other services that we deliver to our students. And so we have to embrace and support its effort to address its budget challenges just we have embraced all these other areas.”[xxi]

To address UC Athletics’ financial situation, Rimai (by then, Interim President) convened an All-University Task Force on Athletics in August 2009. Pres. Rimai’s charge included the following:

Similar to research prominence of renowned faculty, sports play a significant role in building goodwill, respect and recognition for our university as well as providing valuable lessons in teamwork and leadership for our student-athletes. […] [It is imperative that we engage in a thorough assessment and lively dialogue about the role of Athletics in our university community, priorities in an environment of declining state support and how best to sustain Athletics into the future. […] One of the key issues that the Task Force will need to help us figure out is where Athletics fits in with our university budget priorities and how to solve this recurring issue.[xxii]

Note that the Task Force was not to consider whether the Athletics subsidy—and by extension UC’s Division I-FBS status—was sustainable, but rather how to sustain it. Far from promoting a “lively dialogue” about Athletics, the charge was constructed to discourage it. This was no doubt by design. At the June 23, 2009 meeting at which Rimai proposed formation of the Task Force, BOT member Tom Humes made clear that it was:

particularly important not to get into a conversation over what’s most important because if there is a conversation about what’s most important, the academics must always win because the academics drive our institution. But the role that Athletics plays in stimulating and helping the academic and all the other things with the university needs to be looked at. So I think it’s important that the task force look at things not as an either or but how do we join things together and make them collectively more productive.[xxiii]

BOT member Stan Chesley similarly opined: “I think we have to factor in this whole issue of what sports does for the overall university community whether it be students, alumni, or the community and what that brings to us and you can never put the dollars and cents in it, but I really, really feel strongly that part of our plus in raising money for [the] endowment is that fact that we do have an attractive Athletics.”[xxiv]

Given these constraints, it is no surprise that the Task Force’s final report was a muddle. Concluding that “Intercollegiate athletics at UC is important and has been beneficial,” the Task Force listed its benefits, including “increases awareness of UC,” “maintains an important connection with UC alumni,” “helps attract new students to look at UC,” “enhances the college experience for current students,” “builds diversity,” and “increases the likelihood of donations, both to athletics and academics.” [xxv]

The Task Force arrived at these conclusions in part on the basis of a two-page summary of a literature review which itself concluded that evidence of the quantifiable benefits—student applications and enrollment—was “mixed.”[xxvi] Notably, the Task Force downplayed the evidence from its own survey of faculty, students, alumni, and staff “to determine how the university community felt about the athletics program in relation to various other programs at UC.”[xxvii] The Task Force had asked the respondents to

rate the relative importance of ten components of the University’s mission (Faculty, Administration and Leadership, Music and the Arts, Student Life, Intercollegiate Athletics, Community Engagement and Service, Academic Programs and Curriculum, Diversity, Research, and Physical Campus/Buildings and Grounds).[xxviii]

According to the Task Force, each group of survey respondents ranked “Academic Programs” and “Faculty” the highest, and “Intercollegiate Athletics” lowest in importance.[xxix] While they “talked about athletics as being important,” each group of respondents “commented that UC shouldn’t fund athletics at the expense of academics.”[xxx] The Task Force noted only that the survey respondents recommended “balance,” but didn’t elaborate.[xxxi]

With respect to UC Athletics’ finances, the Task Force noted that “revenue follows winning,” but winning clearly was not enough to compensate for several impediments to generating revenue that the Task Force identified, including “a lack of premium revenue amenities and the limited capacity of the football stadium” and a relatively small basketball arena,[xxxii] as well as “a historical lack of interest in UC sports” and “lower benchmark levels of spending to build revenues” (such as on “marketing and fundraising efforts”).[xxxiii] The Task Force also took note of UC Athletics’ “large debt service that was created largely cause of unmet fundraising goals for the Varsity Village project,” and further asserted that “the university did not fully institute a funding model for entering the Big East Conference.”[xxxiv]

Rimai’s charge included the question, “What is the appropriate size of our athletics budget?”, but the range of acceptable answers was clearly limited, given the parameters of the charge itself.[xxxv] So, unsurprisingly, the Task Force did not directly answer this question, stating only that “it could take as much as $11 million additional annually to be competitive in the Big East Conference”, and recommending a “a three-stage plan to appropriately fund athletics”:

- remove the annual deficit,

- pay back the overall deficit, and

- generate the additional revenue and funding to reach the desired level of funding to be competitive in the Big East.[xxxvi]

To help achieve these goals, the Task Force recommended, among other things, increases in student fees, the restoration of approximately $700,000 of the UC Athletics subsidy which had been designed to ensure that UC met NCAA certification standards for Olympic sports scholarships, but which had not been paid in three fiscal years, and the partial or completely assumption of UC Athletics’ deficits.[xxxvii] These recommendations aligned perfectly with the sentiments expressed by Rimai and the BOT members at their meetings.

The Task Force concluded that UC should “maintain a ‘balance’ of priorities for funding athletics, but not at the expense of other important functions.”[xxxviii] The Task Force never actually stated what “balance” actually would look like, particularly if UC found itself (again) in financial straits. Thus, the Task Force never grappled with the hard questions (which might yield unpopular answers), such as whether the UC Administration should prioritize hiring more faculty or paying coaches more money, or which “inadequate facilities” should be renovated first—academic buildings or football stadiums? In a budget squeeze, which is the higher priority? And what if UC can’t do both? Should it drop back to Division II? These questions were left unanswered because Rimai’s charge, reflecting the BOT’s own priorities, kept them off the table.

The UC Faculty Senate responded to the Task Force’s report in a March 11, 2010 resolution recommending that UC Administration “not allocate more general funds money to subsidize the athletic department,” “not assume any portion of the Athletic Department’s accumulated deficit,” and “pursue negotiations for the use of Paul Brown Stadium for all or some portion of the university’s home football games instead of expanding Nippert Stadium.[xxxix] UC Administration did not act upon this resolution. Similarly, UC Administration and the BOT brushed aside faculty concerns expressed four months earlier, when the Faculty representative to the BOT, Marla Hall, had objected to the proposed $10.7 million Jefferson Avenue Sports Complex because faculty had not been consulted and because “it departed from the original plan of waiting to start construction until donations were in hand.”[xl] Unsurprisingly, the Board approved it, with BOT member Jeff Wyler commenting, “The only way we can continue to compete in the Big East and be successful is to get our facilities up to par.”[xli]

2012 and Beyond: Scrambling for a Seat at the High-Rollers’ Table

In February 2013, the Board of Trustees approved the initial stages of the Nippert Stadium expansion, a project that UC Administration was “actively pitching” as it tried to join the Atlantic Coast Conference (“ACC”).[xlii] UC’s desire to join the ACC was fueled in part by the realignment of the Big East conference, which ultimately resulted in the departure of several of the FBS schools to other conferences (such as Rutgers’ entry into the Big Ten, as discussed in Part I), while the remaining football-playing schools formed the American Athletic Conference (“AAC”).[xliii]

At its June 2013 meeting, the BOT gave final approval to the Nippert Stadium renovation project, at a cost of $97,000,000.[xliv] However, UC Administration maintained that “no university general funds are paying for the project. Instead, private donations and premium seating options will fund the project over a period of years.”[xlv] Notwithstanding, over this same time period, the UC Athletics subsidy skyrocketed, topping $20 million in FY13 and reaching an all-time high (for now) of over $25 million in FY14. Incredibly, though, at the June 2013 and June 2014 BOT meetings, Senior Vice President for Administration and Finance Bob Ambach declared that FY13 and FY14 were “break even” years for UC Athletics.[xlvi] Evidently, the era of worrying about UC Athletics’ financial health and self-sufficiency, or at least making a public show of it, was over. Since FY13, the UC Athletics subsidy has never dropped below $20 million.

Following UC’s unsuccessful bid for a place in the ACC, UC made strenuous efforts to gain admission to the Big 12. Around this time, in Fall 2015, the BOT approved design services for the renovation of Fifth Third Arena, and subsequently the project itself, at a total cost of $87 million, $40 million of which would “be raised privately through donations and revenue based bonds with zero state funding”, according to Athletic Director Mike Bohn.[xlvii] Although mention was made of classroom spaces that the renovated Arena would include, clearly the main focus was again on enhancing UC’s attractiveness to a Power Five conference. Responding to concerns from the Faculty Senate representative, Tracy Hermann, about the expense of the project, Board President Rob Richardson stated:

We understand with any investment, there’s always some risk. … [W]e always consider the big picture so we never lose sight of the fact that we are an academic institution but we also made a decision that we are going to be competitive and we are going to make imprint in sports and we think that is also important. … If we don’t make an investment, we do know there will be little chance that we will be able to get into a major conference and doing that will take a lot of burden off of the general fund.[xlviii]

Moving forward on the Fifth Third Arena project ultimately did not win UC a spot in the Big 12. On October 17, 2016, the Big 12 announced that it would not be expanding, leaving UC and other hopefuls out in the cold.[xlix] For the time being, then, UC remains part of the AAC, which currently is trying to raise its stature by rebranding itself as part of the “Power Six” (as opposed to the much less wealthy and prestigious “Group of Five,” which also includes the Mid-American, Mountain West, Sun Belt and Conference USA).” [l]

Later in 2016, the revolving door of football coaches turned once again, when UC’s football team saw the resignation of coach Tommy Tuberville, who had been at UC since 2012 (when he replaced Butch Jones, who in turn had replaced Brian Kelly in 2009). The circumstances of Tuberville’s departure were particularly odd; only two months before he resigned, Tuberville and UC Administration not only had agreed to a two-year contract extension, but also had agreed that Tuberville would receive $2.4 million, or more than double what he would have received, if he were fired after the 2017 season.[li] It is unclear from the public record why UC Administration would agree to a contract extension on such favorable terms, especially since the UC football team had had a 3-3 record at the time the extension was agreed upon.

Conclusion

The story of UC’s entry into Division I-FBS and its significant outlays of money for athletics building projects and subsidies is marked by the failure to fully investigate the assumptions underlying the presumed intangible and tangible benefits of big time intercollegiate athletics—in other words, the failure to separate emotion from fact. Lost in these discussions are fundamental questions: isn’t there a more cost-effective way for UC to market itself, without paying coaches millions, subjecting itself to the whims of Power Five conferences which may never open their doors, and staking its prospects on the hope of winning seasons? Isn’t it possible to build community and school spirit in other ways? UC’s colleges are held to stringent expectations that they meet revenue targets, through the “Performance-Based Budgeting” process, even having to pay back “loans” to the Provost office when they run deficits. UC Athletics appears to be insulated from such expectations, as talk of paying back its deficit has long since quieted. That this inequity remains unquestioned, at least publicly, among UC Administration is alarming, and carries potentially even more expensive consequences as UC tries to spend its way to athletic glory.

[i] University of Cincinnati Financial Report to the NCAA, 2006.

[ii] University of Cincinnati Financial Report to the NCAA, 2016.

[iii]University of Cincinnati Financial Reports to the NCAA, 2006-2016.

[iv] Minutes of the Meeting of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees, November 26, 2002.

[v] Id.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Id.

[viii] Minutes of the Special Meeting of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees, November 5, 2001.

[ix] Minutes of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees, November 5, 2001.

[x] University of Cincinnati Current Funds Budget Plan, FY 2002-2003, p. 53.

[xi] Dow, Dustin. “Big East a Big Leap for UC.” Nov. 4, 2003. www.cincinnati.com.

[xii] Schlabach, Mark. “Cincinnati Orders Huggins to Resign Today or Be Fired.” August 24, 2005. www.cincinnati.com.

[xiii] Koch, Bill. “Cronin Takes Over Bearcats.” March 24, 2006. www.cincinnati.com.

[xiv]Minutes of the Meeting of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees, June 27, 2006.

[xv] Id.

[xvi] Id.

[xvii] University of Cincinnati Current Funds Budget Plan 2002-2003 at 4, 2005-2006 at 4.

[xviii] Koch, Bill. “UC Hires Central Mich. Coach.” December 4, 2006. www.cincinnati.com.

[xix] Cincinnati Bearcats School History. Retrieved from: https://www.sports-reference.com/cfb/schools/cincinnati/

[xx] Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees, June 24, 2008.

[xxi][xxi] Id.

[xxii] All-University Athletics Task Force Report, January 4, 2010, at 2.

[xxiii] Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees, June 23, 2009.

[xxiv] Id.

[xxv] Id. at 7.

[xxvi] Id. at Appendix 8.

[xxvii] Id. at 6.

[xxviii] Id.

[xxix] Id.

[xxx] Id.

[xxxi] Id.

[xxxii] Id.

[xxxiii] Id.

[xxxiv] Id. at 4.

[xxxv] Id.

[xxxvi] Id. at 8.

[xxxvii] Id. at 9-10.

[xxxviii] Id. at 7.

[xxxix] Proposed Faculty Senate Resolution Regarding the Recommendations of the Athletics Task Force, approved March 11, 2010. Retrieved from: http://www.uc.edu/facultysenate/governance.html.

[xl] Peale, Cliff. “UC Athletic Complex Gets OK.” November 18, 2009. The Cincinnati Enquirer. www.cincinnati.com.

[xli] Id.

[xlii] Peale, Cliff. “UC Hopes Overhaul of Nippert Woos ACC.” February 19, 2013. The Cincinnati Enquirer. www.cincinnati.com.

[xliii] “New Name in College Sports: Current BIG EAST Enters New Era as ‘American Athletic Conference.” April 3, 2013. Retrieved from: https://web.archive.org/web/20130406033911/http://www.bigeast.org/News/tabid/435/Article/243706/new-name-in-college-sports-current-big-east-enters-new-era-as-american-athletic.aspx.

[xliv] Minutes of the Meeting of the Board of Trustees, June 25, 2013.

[xlv] Bach, John. “Nippert Stadium Update.” October 2013. UC Magazine.

[xlvi] Minutes of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees, June 25, 2013 and June 23, 2014.

[xlvii] Minutes of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees, August 25, 2015 and December 15, 2015.

[xlviii] Minutes of the University of Cincinnati Board of Trustees, August 25, 2015.

[xlix] Williams, Jason. “UC Officials: ‘Stand with Us as We Fight On.” October 17, 2016. The Cincinnati Enquirer. www.cincinnati.com.

[l] Groeshen, Tom. “UC Is Part of ‘Power 6’ AAC Plan.” July 18, 2017. The Cincinnati Enquirer. www.cincinnati.com

[li] “Buyouts Higher for UC in New Deal for Tuberville.” October 14, 2016. The Cincinnati Enquirer. www.cincinnati.com.

—Stephanie Spanja, J.D.

Director of Research, UC Chapter AAUP