- Click here to read the President’s Corner

- Click here to read Following the Money, Part II

- Click here to read Performance Based Budgeting, Seven Years Later: Decision-Making Inside the Black Box

- Click here to read Evolving Intellectual Property Law Raises Questions about Copyright of Faculty Work, Online Courses

President’s Corner

It has been a difficult year for higher education. The president has appointed a secretary of education whose experience and focus is dismantling public education. The president’s proposed travel ban has created fear and uncertainly at universities throughout the country. Neil Gorsuch has been appointed to the Supreme Court, which will once again take up the “fair share” fees issue (Friedrichs round 2) as the National Right to Work Legal Defense Fund looks to file a petition with the Court this month.

Just last week, the Ohio House passed a heavily amended budget bill (HB 64) that has specific provisions targeting faculty, including: requiring post-tenure review at least once every five years; prohibit colleges and universities from providing sick leave greater than what is in the statute, either on their own accord or via a collective bargaining agreement (which would reduce UC faculty sick leave by one-third); require every faculty member that assigns textbooks to fill out an annual financial disclosure form and pay a filing fee.

With all of these controversial issues surrounding higher education, we have only two options to choose from. Accept defeat or fight. I, for one, choose to fight.

It is heartening to see other faculty fighting too. On April 22nd dozens of faculty, many wearing AAUP T-shirts, participated in the March for Science in Cincinnati. There were companion events in Washington D.C. and across the country. (AAUP-UC was an event sponsor.)

On May 5th, a delegation of AAUP-UC members was in Columbus. They distributed copies of the Ohio Conference biennial higher education report to state legislatures and explained the purpose and necessity of tenure at Ohio’s universities.

Join the fight. The House budget bill now goes to the Senate with all the ant-faculty provisions described above. Contact your Senator using this link. It is quick and easy.

In June when the AAUP-UC delegates are in Washington, D.C. for the AAUP annual meeting they, along with our colleagues from across the country, will be on Capitol Hill discussing higher education issues with elected officials and their staffs.

And, as has been previously announced, in July the AAUP will be hosting its Summer Institute here at the University of Cincinnati. It’s an honor that the AAUP chose UC and I believe it is a reflection on the UC Chapter’s standing and reputation in the AAUP. The Summer Institute is a unique opportunity to meet higher education advocates from across the country. If you have never attended this is obviously a great and convenient opportunity.

These are difficult times, but we are demonstrating that collectively we can make a difference. The AAUP is an effective organization and we are one of the stronger chapters, but we can and must be stronger. If you are not yet a member, join the AAUP-UC Chapter today. If you are a member, talk to a colleague about joining. The difference between the fair share fee and membership dues is minimal, but the impact of membership is tremendous.

Following the Money: The Big Picture: Part II

In the last issue of Works, we examined spending in UC’s colleges and UC Libraries from Fiscal Year 2008-2009 (“FY09”) to Fiscal Year 2015-2016 (“FY16”), a period during which student FTEs increased dramatically, but the majority of college budgets not only failed to keep up with that growth, and some fell significantly behind.[i] Using the same resources—the University’s Annual Fund Accounting Schedules for these same years—we will now take a look at spending in other, non-academic sectors.

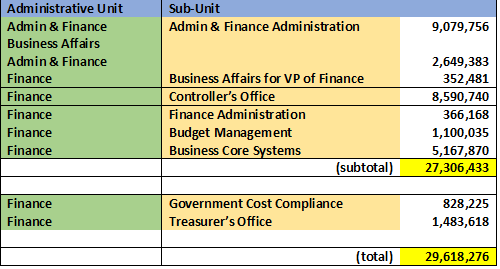

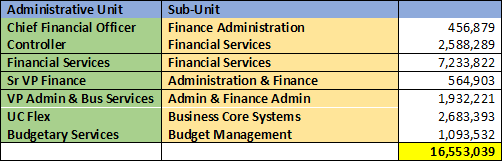

Tracking spending is more challenging in some administrative sectors than others, because they appear in different categories over the years, so a little guesswork is involved. This is especially the case with those sectors having to do with UC’s financial and business operations. Charts I.A. and I.B. detail total spending in the financial sectors in FY09 and FY16, respectively. The different categorizations of the various operations necessitate separate charts, but the intent here is to paint as clear a picture as possible of spending in the University’s business and financial sectors in this time period. In Chart I.B., the sub-units “Government Cost Compliance” and “Treasurer’s Office” are listed separately because they are relatively new and did not appear in any discernable form in FY09. However, they appear to be sufficiently related to the University’s business and finance operations to merit inclusion in the chart.

CHART I.A. – Total Expenditures in the Business and Financial Sectors, FY09[ii]

CHART I.B. – Total Expenditures in the Business and Financial Sectors, FY16

From FY09 to FY16, total expenditures on the University’s business and financial operations skyrocketed by 79%. A deeper dive into that spending suggests that the majority of that increase is attributable to a rise in operating expenditures, rather than salaries (which still rose by a little over a $1 million from FY09 to FY16). One category of spending in the Administrative and Finance Administration sub-unit of Administration and Finance Business Affairs grew dramatically from FY13 to FY16—“Fundraising Activities.” In FY13, Administration Finance and Business Affairs spent $69,592 (in inflation-adjusted dollars) on “Fundraising Activities.” By FY16, this figure ballooned to $7,331,676—and the entire amount went to the UC Foundation.

Interestingly, the UC Foundation appears on the University’s Schedules sporadically from FY13 to FY16 as a separate category of spending, but in amounts of less than $5,000 per year. There is another category having to do with fundraising activities, named, aptly enough, “Professional Services and Fundraising.” This was once housed in the Alumni Office and became its own separate category starting in FY13. Inflation-adjusted expenditures on “Professional Services and Fundraising” gradually dropped from approximately $12.8 million (in inflation-adjusted dollars) in FY09 to $9.1 million in FY16. So, although spending on “Professional Services and Fundraising” has dropped over this time period, when the expenditures on the UC Foundation are factored in, overall spending on fundraising activities has increased by roughly 25%.

It is not clear at this point why the UC Foundation received over $7.3 million in University funds in FY16. It is an odd juxtaposition, however, with the perpetual budget crunches at the colleges, particularly under the PBB regime, which fundraising ideally should be ameliorating, rather than exacerbating.

[i] “Following the Money: The Big Picture, Part I,” Works, Vol. 24, No. 2, 2 March 2017.

[ii] FY09 dollar figures adjusted for inflation using the CPI Inflation Calculator, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

—Stephanie Spanja, J.D.

Director of Research, UC Chapter AAUP

Performance Based Budgeting, Seven Years Later: Decision-Making Inside the Black Box

Performance Based Budgeting, Seven Years Later: Decision-Making Inside the Black Box

It’s probably safe to say that most people see transparency in public institutions as a good thing. When constituents have access to clear, comprehensible information as to how public institutions operate, they are better able to hold public administrators accountable for their decisions.

One of the selling points of Performance-Based Budgeting at UC has been transparency. Through PBB, college revenues and expenditures are determined by using a specific formula, which makes it possible to see exactly how the final dollar amounts were calculated. The virtue of PBB is that it is supposed to leave no room for behind-the-scenes politicking for funding—at least as far as the colleges are concerned. However, there is one aspect of the PBB process which is not transparent: the part in which the decision makers determine how much each college and administrative unit should receive to fund their operations in the coming fiscal year. These decisions are of primary importance, determining how much revenue the colleges are expected to take in to meet those requirements. And yet, as we will discuss, they appear to be made inside the “black box,” where it is unclear exactly who is being consulted, and what specific value judgments have been made.

Moreover, the fact that several aspects of PBB are transparent does not mean that PBB is fair. As we discussed previously, while PBB has an internal logic, it allows for outcomes which are significantly inconsistent across the colleges, with some colleges’ budgets nearly keeping pace with student enrollment increases, while others fall significantly behind.[i] This is so partly because, again, PBB is a top-down process, in which college budgets are determined without sufficient consideration of the colleges’ actual needs and respective capacities to generate higher revenue through increased enrollments. This has facilitated the gradual redistribution of funding away from colleges and increasingly toward administrative sectors.

The PBB Process: A Brief Overview

The PBB process begins in early fall of each year, when the President and the Provost, “through consultation with the Budget Committee (BC) and other stakeholders,” determine how much money the University will need to operate and the University’s projected revenue for the coming fiscal year.[ii] The BC is chaired by the Senior Vice President for Finance and Administration, and includes senior administrators within Finance and the Provost Office, as well as the Associate Dean for Medical Operations and Finance.[iii] It is unclear exactly which other stakeholders are consulted, be they Deans or faculty members, or to what extent they have input. This is the “black box” part of PBB, in which the process of determining those needs is not at all transparent, but opaque.

Bear in mind that, in PBB, the colleges are the primary “revenue producers,” i.e., generators of revenue for the University. Other units that support the colleges, but that do not themselves generate revenue, are “revenue supporters.” This includes administrative units such as the Registrar, Finance, and the President’s Office.[iv]

When the amount of money needed for the University to operate exceeds its anticipated revenue (as it inevitably does), the gap between the two is called a “threshold.”[v] Through various formulas, a share of this threshold is assigned to each college in proportion to their instructional FTEs, major FTEs, and full-time faculty and staff. Shortly thereafter, each college must present a plan for meeting its share.[vi] This plan may include increasing enrollment (and thus tuition revenues), decreasing expenditures (“cost savings and efficiencies”), or a combination of the two.[vii] At the end of the fiscal year, if the college actually takes in more revenue than is necessary to meet its threshold, then it will split an undefined, “agreed upon percentage” of that revenue with the Provost office. If a college fails to meet its threshold share, then its budget will be cut.[viii]

It might be easier to see how this works if we imagine a simple example. Say that University Y is comprised of 2 colleges: A and B. Through a PBB process, University Y has determined that it needs $110 million to operate. However, it projects that A and B will only bring a combined total of $105 million in revenue, leaving a $5 million short fall. This $5 million is the threshold. By headcounts of FTEs, full-time faculty and staff, College A is deemed to be the larger of the two colleges (and a larger consumer of University resources, such as administrative support and maintenance). So, College A is assigned $3 million as its threshold share, and College B is assigned $2 million. Colleges A and B now have to submit plans for how they will meet their thresholds, either by cutting budgets or through growth. If they fail to meet their shares, then their budgets will be cut. If they exceed their shares, they will split a portion of the excess profit with University Y.

PBB’s Impact on the Colleges

We have already seen the disparities between increased student enrollments and lagging college budgets, the latter of which is in large part the product of the PBB process.[ix] We have also observed, on the basis of a review of the threshold plans and budgets through FY15, that PBB has had multiple negative impacts on several colleges, including, among others:

- Discouraging the hiring of full-time faculty and the replacement of retiring faculty;

- Increased class sizes;

- Reduced staff support; and

- Increased student fees for some programs.[x]

When we examine exactly how much the colleges are allocated through the PBB process, in relation to the revenues they generate, it is not hard to see how such outcomes are possible. Indeed, they are necessitated by the PBB model, which is predicated upon assigning each college a threshold share—or built-in budget deficit—that they must climb out of through more revenues or budget cuts.

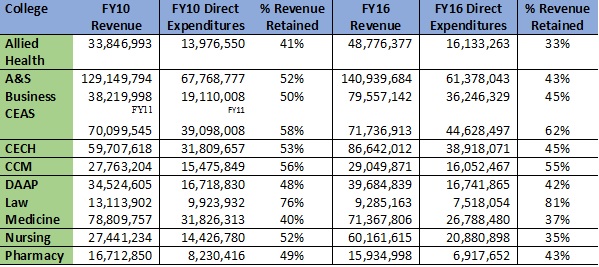

“Direct expenditures” are those portions of revenue from tuition, fees, and State Share of Instruction (SSI) that colleges retain control over. Chart I below shows that, in inflation-adjusted dollars, most colleges retained, or were allowed to keep, smaller proportions of this revenue, in FY16 as compared to FY10, even adjusting for inflation.[xi] It is important to note that “direct expenditures” here do not include funds derived from other sources, including grants, endowment funding, etc., so the figures below do not correspond with the “Total Expenditures” referenced in the Annual Fund Accounting Schedules.[xii] Nonetheless, the data below is a revealing barometer of the impact of PBB on college operations.

Note that although UC Blue Ash and UC Clermont submit budget plans through the PBB process, they are separately budgeted and thus are not included in the PBB model. Also, data for the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences is provided as of when it was first available, in FY11, following the merger of the College of Applied Sciences into the College of Engineering.[xiii]

Chart I: Total Net Revenues and Direct Expenditures by the Colleges, Compared

More Money for Administrative Sectors

Only two colleges retained a larger proportion of their revenue in FY16 than they did in FY10: CEAS and Law, though in the latter case the dollar amount was actually lower in FY16 than in FY10, due to a market-wide drop in enrollment. Among the majority of colleges which retained less of their revenue in FY16 than in FY11, A&S stands out for a particularly startling result: it sustained not only a percentage drop in the revenue it retained, but also a drop in the actual dollars it retained—despite seeing an increase in its revenue and, as we reported previously, a 25% increase in its FTEs.[xiv]

Chart I suggests that, under PBB, there has been a dramatic redistribution of money away from the colleges and toward various administrative and other support sectors. This is borne out by other data from the Revenue and Cost Templates.

Total net revenues generated by the colleges grew from approximately $545 million in FY10 (adjusted for inflation) to $658 million in FY16, a nearly 21% increase. [xv] However, the amount of revenues that the colleges retained control over as “direct expenditures”, presumably used to directly sustain their operations, only increased by 6%, rising from $281 million in FY10 (in inflation-adjusted dollars) to $298 million in FY16. Meanwhile, revenues used to support the University’s operations (“indirect expenditures”) increased from $266 million in FY10 (in inflation-adjusted dollars) to $359 million in FY16, a 35% increase.

Chart II below displays the changes in indirect expenditures from FY10 to FY16. It is important to note that most colleges’ direct expenditures, as listed in the Revenue and Cost Templates, include spending in several of the categories listed below, although the vast majority are devoted to Instruction, with the next largest category being Academic Support (which includes expenses for Deans’ offices). It is unclear from the Primer what would distinguish an “indirect expenditure” on Instruction from a “direct expenditure.”

Chart II: Indirect Expenditures under PBB

While the largest percentage increase is in Instruction, the largest dollar increase, by far, is in institutional Support, which grew by nearly $36 million dollars from FY10 to FY16, followed close behind by the category “Unassigned,” with a $28 million dollar increase over the same period. Institutional Support is comprised of a long list of administrative units, including the President’s Office, Legal Affairs and General Counsel, University Health Services, Finance Administration, and Human Resources, among several others. It is not yet clear exactly where the “Unassigned” funds were eventually assigned to and how they were spent; this merits further investigation.

Conclusion

It is reasonable to speculate that, if one were to try to run a University “like a business,” at least in terms of its finances, then PBB would be the budgetary tool of choice. It is profit-driven, concerned with short-term outcomes, indifferent to the particular needs of the sub-units, and provides a conduit for directing more money upward—or at least away from the sectors that generate the revenue, i.e., the colleges. Colleges can’t do their jobs, of course, without administrative support structures. However, whereas 52% of revenues went to the colleges as “direct expenditures” in FY10, by FY16 this proportion dropped to 46%, with the “indirects” taking the rest. This is a significant movement of funding away from the core academic mission.

A robust discussion about the University’s budget priorities should include Deans, Faculty Senate, faculty members at-large, and other stakeholders, and could result in very different outcomes than those under PBB. But for that to happen, the decision-making process about each college’s and administrative unit’s actual needs must be taken out of the “black box” in which it currently exists.

[i] “The More Things Change …: UC Instructional Spending Still Lagging, Despite Increased Enrollment,” Works, Vol. 23, No. 5, 15 Dec. 2016.

[ii] Primer on PBB and the Revenue and Cost Template, Fiscal Year 2017, Revised 3/30/17, available through the Office for Institutional Research.

[iii] http://www.uc.edu/provost/faculty1/committees/Budget_Committee.html, Accessed Web 1 May 2017.

[iv] Primer, supra.

[v] Id.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Id.

[viii] Id.

[ix] “The More Things Change,” supra.

[x] “PBB: The High Cost of ‘Efficiency,” Works, Vol. 22, No. 5, 3 Sept. 2015.

[xi] University of Cincinnati, Revenue and Cost Templates, Fiscal Year 2010 ,Version 9.0, Fiscal Year 2011, Version 4.1 and 2016, Version 4.1. The latest know version of each Revenue and Cost Template was used for this article. Dollar figures for FY10 inflation-adjusted using CPI Inflation Calculator, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

[xii] See “The More Things Change,” supra.

[xiii] Data for the College of Allied Health Sciences in FY10 includes figures for the then-separately budgeted College of Social Work, which was merged completely into Allied Health the following year.

[xiv] “The More Things Change,” supra.

[xv] University of Cincinnati, Revenue and Cost Templates, Fiscal Years 2010 and 2016; dollar figures for FY10 inflation-adjusted using CPI Inflation Calculator, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

—Stephanie Spanja, J.D.

Director of Research, UC Chapter AAUP

Intellectual Property Law Raises Questions about Copyright of Faculty Work, Online Courses

Intellectual Property Law Raises Questions about Copyright of Faculty Work, Online Courses

The AAUP-UC Chapter receives a number of questions from faculty about copyright ownership of their academic work product, especially with regard to online or distance learning. This is undoubtedly a reflection of the recent explosion of distance learning across UC, and the involvement of outside entities in distance learning endeavors (by marketing or recording on-line courses, or by possibly playing some role in their development). Faculty want to know: when I upload my course materials to Blackboard (or some other online platform), do I still own those materials?

Here, we present a basic overview of copyright law, a discussion of the national AAUP’s position regarding copyright ownership in academia, and a review of UC’s policy on copyright ownership. We’ll provide a full review of this complex and evolving area of law, and recommendations for faculty engaged in distance or online learning, in a Staff Advisory Letter which will be issued at the beginning of the Fall Semester.

Copyright Law and Faculty: The Basics

The Copyright Act of 1976 “protects original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium. See 17 U.S.C. § 102. This includes books, private letters, paintings, computer programs, motion pictures and other audiovisual work. It also includes anything else fixed, no matter how it is fixed … [such as] web pages [and] notes on a scrap of paper.” (Works, 15.8, 1 Dec. 2008, “Copyright in Academia,” p. 1.) As noted in that article, copyright can be asserted once the work is fixed in a tangible medium, and registration [of the copyright] is not necessary to create the copyright protection. The holder of a copyright owns not only the work, but the right to control its use, including the right of reproduction, translation, abridgment, revision, public distribution, public performance and display.

One statutory exception to these basic rules of copyright ownership is the “work-for-hire” doctrine, which entitles an employer to assert ownership of materials prepared by its employees acting within the “scope of their employment.” The “work-forhire” doctrine has been in existence since the 1909 Copyright Act. However, the work-for-hire exception had its own exception under the common law: the “teacher’s exception,” under which “work-for-hire had not applied to faculty members’ academic writings.” (Garon, Jon. “The Electronic Jungle: The Application of Intellectual Property Law to Distance Education, 4 VAND. J. ENT. L. & PRAC., 146, 152, (Spring 2002)).

Since the Copyright Act of 1976 was established, the continued existence of a “teacher’s exception” under the law is seriously in doubt, at best. However, the justification for such an exception in practice continues to be valid, as not only asserted by the National AAUP, but also reflected in the fact that numerous institutions, including UC, expressly disclaim copyright ownership of most works created by faculty (as well as those by staff and students).

The National AAUP’s Position on Faculty Copyright Ownership

In its 1999 Statement on Copyright, the National AAUP noted:

the prevailing academic practice [of treating] the faculty member as the copyright owner of works that are created independently and at the faculty member’s own initiative for traditional academic purposes. Examples include class notes and syllabi; books and articles; works of fiction and nonfiction; poems and dramatic works; musical and choreographic works; pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works; and educational software[.]

The Statement distinguishes the traditional employer-employee relationship for which the “work-for-hire” exception is tailored (in which the employer directs the form and content of the material produced) from the environment in which “traditional academic works” are produced, in which “the faculty member rather than the institution determines the subject matter, the intellectual approach and direction, and the conclusions.” As the Statement affirms: “This is the very essence of academic freedom.”

Copyright and University Policy

UC has expressly disclaimed copyright ownership of “traditional works” in Board Rule 10-19-02(B)(1):

The policy does not change the traditional relationship between the university and authors of textbooks and other scholarly and artistic works. Unless the production of such materials is subject to paragraphs (B)(2) to (B)(4) of this rule, the university disclaims ownership of copyrights in textbooks, monographs, papers, articles, musical compositions, works of art and artistic imagination, unpublished manuscripts, dissertations, theses, popular nonfiction, novels, poems and the like that are created by its faculty, staff and students.

The three exceptions to this Rule are:

- Externally sponsored works. In such cases, copyright ownership is determined “as part of the ordinary contracting process that relates to externally sponsored projects.” (B)(2)

- University sponsored works. In subsection (B)(3) of the Board Rule, UC claims copyright ownership over materials specifically produced as “works-for-hire,” including “works created as a result of specific assignments; works supported by a direct allocation of university funds for the pursuit of a specific project; and works that are specially commissioned by the university. However, (B)(3) makes expressly clear that:

A faculty member’s general obligation to produce scholarly works does not constitute a specific university assignment, nor is the payment of regular salary, the use of office and library facilities, or the production of incidental clerical support or reasonable data and word processing considered a direct allocation of university funds or the purposes of this [subsection].

- University supported work. In subsection (B) (4), UC “claims copyright to works produced with significant use of its resources,” or, in other words, “resources that exceed the normal amount of resources available to faculty, staff and students for the performance of their normal functions.”

Faculty work product such as course design, course syllabi and lecture notes do not fall within any of the above exceptions, since they are not externally sponsored (with rare exceptions). Rather, they are the product of faculty members’ typical workload (not special or unusual assignments), and do not typically involve the “significant use of [University] resources.” Thus, course design, syllabi and lecture notes would be expected under the University’s Board Rules to be “owned” by the faculty member.

Copyright and Distance Learning

From one perspective, on-line instruction is simply another modality of delivering course content. In that light, then, the principles of copyright ownership that apply to course syllabi, lecture notes and materials in a traditional brick-and-mortar course should similarly apply in distance learning courses. However, the national AAUP, in its 1999 Statement on Distance Education, has noted that “systems of interactive television, satellite television, or computer-based courses and programs are technologically more complex and expensive than traditional classroom instruction, and require a greater investment of institutional resources and more elaborate organizational patterns.” In cases where a university has simply supplied the “delivery mechanism” for on-line content (such as “video-taping, editing and marketing services”), “it is very unlikely that the institution will be regarded as having contributed the kind of ‘authorship’“ that would “[entitle] it to a share in the copyright ownership.”

However, the National AAUP noted, an “institution may, through its administrators and staff, effectively determine or contribute to such detailed matters as substantive coverage, creative graphic elements, and the like; in such a situation, the institution has a stronger claim to coownership rights” [emphasis added] and “it is not likely that a single principle of law can clearly allocate copyright-ownership interests in all cases.”

While the National AAUP statement does not supplant or otherwise modify the faculty’s right to control curriculum per Article 27.2 of the AAUP-UC Collective Bargaining Agreement, the reality is that online or distance learning has exploded since the AAUP issued its 1999 Statement, and recent legal decisions have begun to hammer out—or in some cases make more murky—those very questions raised about technological complexity some 15 years ago.

—Stephanie Spanja, J.D.

Director of Research, UC Chapter AAUP