- Click here to view “AAUP-UC 365”

- Click here to view “High Hopes, High Stakes (Part III): UC Doubles Down

- Click here to view “PBB’s Impact on the Colleges”

- Click here to view “CCM under PBB: A Flagship in Distress”

- Click here to view “Survey Announcement”

AAUP-UC 365

AAUP-UC 365

When faculty think of AAUP-UC, most probably think of the contract. The contract is important. Through it, and collective bargaining, the faculty have achieved some tremendous improvements, including increases in faculty development funds, paid parental leave, as well as defeating efforts to impose enormous health insurance fees.

The contract and the benefits and protections that it brings for faculty will continue to be important, but we are more than a Contract. The AAUP-UC cannot effectively counter the powerful institutional and political forces working to degrade the mission and quality of higher education with a membership that is only active every three years at contract-negotiation time. We need a dynamic AAUP-UC that is in continual engagement with the multitude of problems at UC–problems that impact faculty working conditions, problems that interfere with faculty’s ability to produce substantive research and scholarship, and problems that diminish our ability to effectively teach our students. We need an AAUP-UC that is working 365 days a year, every year.

The Associates Council is working to make this happen. We have begun to organize faculty Action Teams that will be asking you to share the problems you face locally, in your department or college, that prevent you from achieving your best as an educator and researcher.

You may, for instance, be frustrated with the inadequacy of the technology or the design of the classroom space where you teach. Perhaps you are experiencing “service creep” that diminishes your effectiveness as a teacher and researcher. Or maybe you have observed, as so many of us have, that your unit’s over-reliance on term-appointed adjuncts rather than faculty with longer-term contracts not only impacts the physical, emotional, and financial health of these instructors, but also the quality of the programs in which they teach.

The goal is to organize around our shared values as a faculty. These Action Teams will work to develop actionable solutions to the issues that impact us “right where we live” within our institution.

If you have a local issue impacting your work that needs to be addressed, or you are interested in becoming a member of an Action Team, please contact us at campagc@ucmail.uc.edu or cassandra.fetters@uc.edu

When AAUP-UC was formed in 1976, the faculty did not gather around a table and say we need a collective bargaining agreement. They gathered to solve a problem. The collective bargaining agreement was just part of the solution to that problem.

The problems at UC are different today but just as numerous as they were in the 1970s. The administration will not solve these problems. The students are not well-positioned to solve these problems. The problems will and can only be solved by we the Faculty.

If you want to discuss a specific problem or are ready to take action, please contact us, or an Associate in your college.

Chris Campagna, Chair, AAUP-UC Associates Council

Cassie Fetters, Vice-Chair, AAUP-UC Associates Council

High Hopes, High Stakes (Part III): UC Doubles Down

Beginning FY 2006, […], the [athletics budget] will be balanced due to the [Big East’s] lucrative revenue sharing. […] In subsequent years, the [athletics] deficit fund balance will be repaid, thus eliminating the deficit by FY 2012. University Current Funds Budget Plan, FY 2004-2005

The multi-year Fiscal Operating Plan projects further deficit reduction in FY 09 and a break-even operation in FY 10. University Current Funds Budget Plan, FY 2007-2008

FY 2011 stands to be another sound fiscal showing as UC Athletics looks to improve upon the planned deficit of previous years and report a $969,000 deficit at year’s end. …The department is on course with a plan for the future that leads to fiscal responsibility, transparency, and strategic spending. University Current Funds Budget Plan, FY 2011-2012

[T]he fiscal outcomes of college athletics continue to be challenging[.] University Current Funds Budget Plan, FY 2015-2016; University Current Funds Budget Plan, FY 2016-2017; University Current Funds Budget Plan, FY 2017-2018

Well over a decade after UC began competing in the Big East in Fall 2005, and after well over a decade’s worth of rosy predictions that UC’s Athletics program not only would break even, but be able to pay back its deficit, the UC Athletics program is carrying over $176 million in athletics facilities-related debt, and the UC Athletics subsidy has ballooned to over $25 million as of FY17.[i]

In Part I of this series, we examined the validity—and lack thereof—of the common justifications for the enormous spending by academic institutions on their athletics programs, particularly Division I–Football Bowl Subdivision (“FBS”) competition.[ii] We saw in Part II how, over the past 15 years, this mythology helped propel and sustain the UC Administration’s massive spending and building spree on its intercollegiate Athletics program.[iii] Now, in Part III, we take a more detailed look at UC Athletics finances, using the data in the annual reports that the Administration submits to the NCAA. This information is far more revealing than what appears in UC’s Annual Fund Accounting Schedules and shows in often stark terms the financial consequences of UC’s venture into Division I-FBS competition.

On the Revenue Side

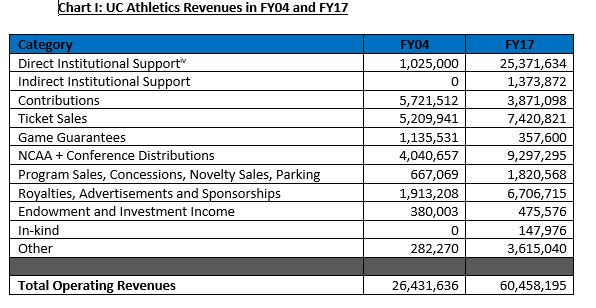

Chart I displays the sources of UC Athletics’ operating revenues from FY04 (one year before it officially began competing in the Big East) through FY17. FY04 dollar figures are inflation-adjusted.[iv] The categories below are defined in the NCAA’s 2017 Agreed-Upon Procedures.[v]

The UC Athletics subsidy now accounts for 42% of the UC Athletics department’s annual revenues, over ten times more than 4% in FY04.[vii] While there have been increases in several other revenue streams, most notably NCAA and conference distributions as well as ticket sales, contributions to UC Athletics have plunged by nearly $2 million since FY04 (after peaking at over $6 million in FY12).[viii]

How UC Athletics’ Dollars Are Spent

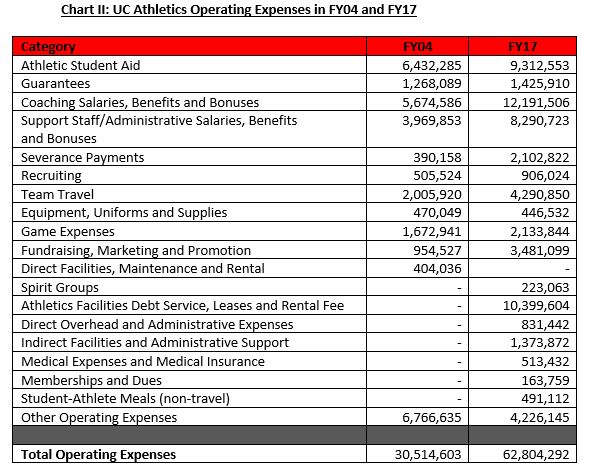

UC Athletics appears to be running a smaller deficit in FY17 (at $2.3 million) as compared with FY04 (at over $4 million) only because the Athletics subsidy has increased so dramatically over that same time. As we observed in Part III of this series, the UC Administration has long abandoned even a public show of hand-wringing over UC Athletics’ finances.[ix]

The most notable hikes in spending relate to UC Athletics personnel: the cost of coaches’ salaries, benefits and bonuses more than doubled from FY04 to FY17, as did the cost of support and administrative staff. Together, coaching and administrative support staff salaries cost over $20 million in FY17. Let’s put this in perspective: the amount that UC spent on coaches’ and Athletics staff compensation in FY17 was only slightly less than the entire FY17 operating expenditures of the College of Design, Architecture, Art, and Planning (“DAAP”) and the College of Allied Health Sciences (“CAHS”) (at roughly $21 million each).[x]

Also, it’s worth noting that, as UC Athletics facilities-related debt skyrocketed to $176 million, the cost of servicing that debt has likewise grown, comprising 16.5% of UC Athletics’ operating expenses in FY17.

A Closer Look at the “Revenue Sports”

As we noted in Part I of this series, one of the common rationales for heavy investments in intercollegiate men’s basketball and football programs is that these are the “revenue sports” which support those programs that usually do not generate enough revenue to be self-supporting (the “non-revenue sports,” e.g., women’s basketball and Olympic men’s and women’s sports.) However, nationwide less than half of men’s basketball and football programs in Division I-FBS were “profitable” in FY15, reflecting a long-term trend.[xi]

From FY09 through FY13, the UC Football program generated revenues over expenses, peaking at a $3 million profit in FY12. From FY14 through FY17, however, the UC Football program has operated deeply in the red, with an average $5 million annual deficit. UC Men’s Basketball has more consistently shown positive revenues, ranging from a low of $89,000 in FY14 to a peak of $1.9 million in FY05. However, in both FY16 and FY17, UC Men’s Basketball ran deficits of approximately $1 million per year. [xii] The notion that either UC Football or UC Men’s Basketball will soon be in a position to consistently support the non-revenue sports is unrealistic, to say the least.

Conclusion: Where Do We Go from Here?

UC Athletics has $176 million in facilities-related debt and flagship programs which are running deficits; it relies heavily on an annual subsidy which tops $25 million, and it is receiving less in contributions than it did in FY04, before UC began competing in the Big East. It is difficult to see how the UC Athletics program can continue to be sustained, and its debt paid off, without continued, significant, and ever-increasing infusions of cash from UC general funds. There are legitimate questions as to the viability of continuing on this path, both for UC’s finances and its academic mission. As reported in “PBB: System of Growing Inequity,” the colleges are held accountable for their deficits and must pay back loans from the Provost office that covered those deficits, regardless of the detrimental impacts of years of manufactured scarcity. UC Athletics is not held accountable for its deficits and continues to receive more and more money from the Administration. It is long past time for the Administration to confront this deteriorating situation with realism, and to acknowledge and correct the disparities in the way that it treats the UC Athletics program and its colleges.

[i] University of Cincinnati FY2017 NCAA Report (2017).

[ii] Spanja, S. (2017, October 2017). High Hopes, High Stakes: Division I Athletics at UC and the Never-ending Quest for the Big Payday, Part I: The Stakes. Works, 24.

[iii] Spanja, S. (2017, November 2017). High Hopes, High Stakes: Division I Athletics at UC and the Never-ending Quest for the Big Payday, Part II: UC Antes Up. Works, 24.

[iv] https://www.bls.gov./cpi

[v] http://www.ncaa.org/sites/default/files/2017FIN_Agreed_Upon_Procedures_20170515.pdf. Please note that the categories “NCAA Distributions” and “Conference Distributions” are combined in Chart I.

[vi] In FY04, UC student fees accounted for $4 million of UC Athletics revenues. Beginning in FY05, student fees are not represented as a revenue source. University of Cincinnati FY2004 NCAA Report (2004); University of Cincinnati FY2005 NCAA Report (2005.)

[vii]Note that FY05 marked a dramatic shift in UC-generated funds for UC Athletics; there was no longer a “student fees” revenue stream, and “direct institutional support” increased from $1 million in FY04 to $5.6 million in FY05, and continued to rise ever since.

[viii] University of Cincinnati FY2012 NCAA Report (2012).

[ix] Spanja, S., (November 2017), supra.

[x] University of Cincinnati Annual Fund Accounting Schedules, FY 2017 (2017).

[xi] Spanja, S. (October 2017), supra.

[xii] University of Cincinnati FY2004-FY2017 NCAA Reports (2004-2017).

—Stephanie Spanja, J.D.

Director of Research, UC Chapter AAUP

Performance Based Budgeting: A System of Growing Inequity

Performance Based Budgeting: A System of Growing Inequity

[The following is a revised and updated version of “Performance Based Budgeting, Seven Years Later: Decision-Making Inside the Black Box,” Works, May 9, 2017.]

Sold as a tool that would bring much-needed transparency to UC’s budgeting process, performance based budgeting (PBB) was implemented beginning with Fiscal Year 2010 (“FY10”). PBB is transparent in the sense that it provides a set of clear formulas for distributing revenue among UC’s colleges and administrative units. But when it comes to the process of determining how much money each college and administrative unit will receive to fund their operations in the coming fiscal year, PBB is opaque. The most crucial value judgments, those which directly impact the operations and financial health of colleges—and by extension the quality of the student experience—are made by a few identifiable individuals who consult with other unidentified persons, without any structured or public dialogue with and input from faculty, students, and even Deans.

While PBB has an internal logic, it allows for wildly inconsistent outcomes across the colleges, with some colleges’ budgets nearly keeping pace with student enrollment increases, while others fall significantly behind.[i] The proportion of revenues that colleges are allowed to retain is determined without full consideration of the colleges’ actual needs and without realistic appraisals of their respective capacities to generate higher revenue through increased enrollments. In addition, the top-down PBB process has facilitated the gradual redistribution of funding away from colleges and increasingly toward administrative sectors.

The PBB Process: A Brief Overview

The annual PBB process begins in early fall, when the President and the Provost, “through consultation with the Budget Committee (BC) and other stakeholders,” determine how much money the University will need to operate and the University’s projected revenue for the coming fiscal year.[ii] The BC is chaired by the Senior Vice President for Finance and Administration, and includes senior administrators within Finance and the Provost Office, as well as the Associate Dean for Medical Operations and Finance.[iii] It is unclear exactly which other stakeholders are consulted, be they Deans, faculty members, or others, or how extensive their input may be.

In PBB, the colleges are the primary “revenue producers,” i.e., generators of revenue for the University. Other units that are part of the University’s operations, but that do not themselves generate revenue, are “revenue supporters.” This includes administrative units such as the Registrar, Finance, and the President’s Office.[iv]

When the amount of money needed for the University to operate exceeds its anticipated revenue (as it inevitably does), the gap between the two is called a “threshold.”[v] A share of this threshold is assigned to each college in proportion to their instructional FTEs, major FTEs, and full-time faculty and staff. Shortly thereafter, each college must present a plan for meeting its share.[vi] This plan may include increasing enrollment, proposing fee increases, decreasing expenditures (“cost savings and efficiencies”), or a combination of the three. At the end of the fiscal year, if the college takes in more revenue than is necessary to meet its threshold, then it will split an undefined, “agreed upon percentage” of that revenue with the Provost office. If a college fails to meet its threshold share, then its budget will be cut.[vii] (Note that the process by which colleges present their threshold plans is the only official input that the colleges have in the PBB process, and that this process occurs only after their threshold shares have been determined.)

It might be easier to see how this works if we imagine a simple example. Say that University Y is comprised of 2 colleges: A and B. Through PBB, University Y has determined that it needs $110 million to operate. However, it projects that A and B will only bring a combined total of $105 million in revenue, leaving a $5 million short fall. This $5 million is the threshold. By headcounts of FTEs, full-time faculty and staff, College A is deemed to be the larger of the two colleges (and a larger consumer of University Y’s resources, such as administrative support and maintenance). So, College A is assigned $3 million as its threshold share, and College B is assigned $2 million. Colleges A and B now have to submit plans for how they will meet their thresholds, either by cutting budgets or through growth. If they fail to meet their shares, then their budgets will be cut. If they exceed their shares, they will split a portion of the profits with University Y.

PBB’s Impact on the Colleges

We have already seen the disparities between increased student enrollments and lagging college budgets, the latter of which is in large part the product of the PBB process.[viii] We have also observed that PBB has had multiple negative impacts on several colleges, including, among others:

- Discouraging the hiring of full-time faculty and the replacing of retiring faculty;

- Increased class sizes;

- Reduced staff support; and

- Increased student fees for some programs.[ix]

These outcomes are not accidental by-products of PBB. Rather, they are encouraged, sometimes explicitly, in the PBB process. We can see the financial impacts on the colleges by looking at changes over the years in how much of their revenues they have been able to keep—and how much has been designated for administrative and other sectors.

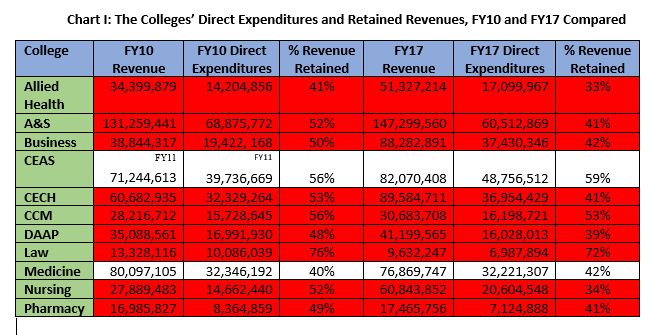

In PBB-speak, “direct expenditures” are portions of revenue from tuition, fees, and State Share of Instruction (SSI) over which colleges retain control. Chart I below shows that, in inflation-adjusted dollars, most colleges retained, or were allowed to keep, smaller proportions of this revenue, in FY17 as compared to FY10, even adjusting for inflation.[x] To be clear, “direct expenditures” do not include funds derived from other sources, including grants, endowment funding, etc., so the figures below do not correspond with the “Total Expenditures” referenced in the Annual Fund Accounting Schedules that are produced by the University’s Controller’s Office.[xi] Nonetheless, the data below is a revealing barometer of the impact of PBB on college operations.

Note that although UC Blue Ash and UC Clermont submit budget plans through the PBB process, they are separately budgeted and thus are not included in the PBB model. Also, data for the College of Engineering and Applied Sciences is provided as of when it was first available, in FY11, following the merger of the College of Applied Sciences into the College of Engineering.[xii]

As Chart I shows, the vast majority of colleges saw percentage decreases in their direct expenditures (retained total net revenue), despite increases in their total net revenues. Moreover, A&S, DAAP and Pharmacy retained less money in direct expenditures in FY17 than they did in FY10. The case of A&S is especially egregious: despite taking in $16 million more in total net revenues from FY10 to FY17, the amount that A&S was able to keep as direct expenditures actually dropped by $8 million.

The following bullet-points below provide a view of the overall impact on direct expenditures under PBB, and include dollar figures from the Division of Experience-Based Learning and Career Education, as well as the now-defunct College of Applied Science and the Center for Access and Transition:

- Total net revenues generated by the colleges in FY10: $554 million

- Direct expenditures (revenue retained by colleges) in FY10: $285 million

- Percentage of total net revenues retained by the colleges as direct expenditures in FY10: 51%

- Total net revenues generated by the colleges in FY17: $700 million

- Direct expenditures (revenue retained by colleges) in FY17: $307 million

- Percentage of total net revenue retained by colleges as direct expenditures in FY17: 44%

- Dollar increase in total net revenues generated by the colleges, FY10 to FY17: $146 million

- Ratio of additional total net revenue to additional direct expenditures: 6.6:1

So, for nearly every $7 in additional revenue that the colleges generated in FY17 over FY10, the colleges were able to keep $1. This begs the question: where did the rest of the money go?

More Money for Administrative Sectors

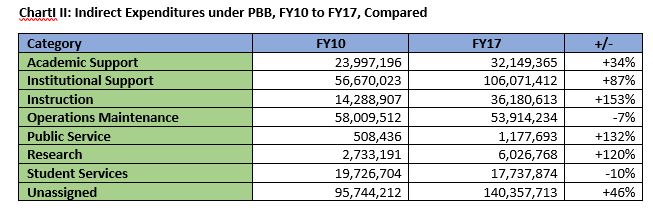

Under PBB, there has been a dramatic redistribution of money away from the colleges and toward administrative and other sectors. Chart II below displays the changes in indirect expenditures from FY10 to FY17. It is important to note that most colleges’ direct expenditures include some spending in several of the categories listed below, but the vast majority are devoted to Instruction, with the next largest category being Academic Support (which includes expenses for Deans’ offices). (It is unclear from the PBB Primer as to what distinguishes an “indirect expenditure” on Instruction from a “direct expenditure.”)

While the largest percentage increase is in Instruction, the largest dollar increase, by far, is in Institutional Support, which grew by nearly $50 million dollars from FY10 to FY16, followed close behind by the category “Unassigned,” with a $44 million dollar increase over the same period. Institutional Support is comprised of a long list of administrative units, including the President’s Office, Legal Affairs and General Counsel, University Health Services, Finance Administration, and Human Resources, among several others. It is not yet clear exactly where the “Unassigned” funds were eventually assigned to and how they were spent.

Conclusion

If one wanted to run a University “like a business,” then PBB would be the budgetary tool of choice. It is profit-driven, concerned with short-term outcomes, indifferent to the particular needs of the sub-units, and provides a conduit for directing more money upward—or at least away from the sectors that generate the revenue, i.e., the colleges. Colleges can’t do their jobs, of course, without administrative support structures. However, whereas 51% of revenues went to the colleges as “direct expenditures” in FY10, by FY17 this proportion dropped to 44%, with the “indirects” taking the rest. This is a significant movement of funding away from the core academic mission.

A robust discussion about the University’s budget priorities should include Deans, Faculty Senate, faculty members at-large, and other stakeholders, and could result in very different outcomes than those under PBB. But for that to happen, the decision-making process about each college’s and administrative unit’s actual needs must be taken out of the “black box” in which it currently exists.

[i] Spanja, S. (2016, December 2016). The More Things Change …: UC Instructional Spending Still Lagging, Despite Increased Enrollment,” Works.

[ii] Primer on PBB and the Revenue and Cost Template, Fiscal Year 2018, Revised 3/30/17, 5, available through the Office for Institutional Research.

[iii] http://www.uc.edu/provost/faculty1/committees/Budget_Committee.html, Accessed Web January 29, 2018.

[iv] Primer, supra, at 4.

[v] Id. at 2.

[vi] Id.

[vii] Id.at 6.

[viii] Spanja, S., supra.

[ix] Spanja, S., (2015, September 2015). PBB: The High Cost of ‘Efficiency, Works.

[x] University of Cincinnati, Revenue and Cost Templates, Fiscal Year 2010, Version 9.0; Fiscal Year 2011, Version 4; 2016, Version 4.1; and Fiscal Year 2017, Version 4.1. The latest known version of each Revenue and Cost Template was used for this article. Dollar figures for FY10 and FY11 were inflation-adjusted using CPI Inflation Calculator, https://data.bls.gov/cgi-bin/cpicalc.pl.

[xi] Spanja, S., The More Things Change, supra.

[xii] Data for the College of Allied Health Sciences in FY10 includes figures for the then-separately budgeted College of Social Work, which was merged completely into Allied Health the following year.

—Stephanie Spanja, J.D.

Director of Research, UC Chapter AAUP

CCM under PBB: A Flagship in Distress

CCM under PBB: A Flagship in Distress

UC Magazine recently celebrated the history and achievements of the College-Conservatory of Music (“CCM”) in “Setting the Stage for CCM’s Sesquicentennial.”[i] At the same time that the Administration is promoting and publicly praising CCM, one of the jewels in UC’s crown, however, it is undermining CCM by using a budgeting system—PBB—which has placed CCM in a near-constant state of financial crisis since FY10.

In “PBB: The High Cost of Efficiency,” Works, September 3, 2015, we examined the impacts of PBB on specific colleges, including CCM. For several years, CCM administrators repeatedly tried to explain to the Provost office that CCM’s physical space, already-over capacity, limited its ability to bring in more revenue through enrollment growth. Moreover, those within CCM pointed out, the highly-specialized, interdependent and one-on-one instruction intrinsic to its mission necessitated maintaining and even increasing its faculty complement, given the strain on current faculty who were carrying well above standard workloads.[ii] As far as we can tell, there have been no adjustments to the PBB model to accommodate CCM’s unique needs.

According to documents provided by a CCM faculty member who preferred not to be identified, In FY17, CCM had a $1.187 million budget shortfall. This was due in significant part to normal student attrition between Fall 2016 and Spring 2017—normal, but nonetheless devastating to the CCM budget under the PBB regime, which automatically punished CCM with a budget reduction of $979,000. CCM received a bridge loan of $540,821 from the Provost office to cover expenses, and according to the CCM faculty member, made up the remainder of its budget deficit in part by increasing student enrollment through non-major courses and by slashing adjunct pay. To make ends meet, CCM has also had to resort to drawing down from its endowment; from FY15 projected through FY18, CCM’s endowment has dropped by $1.7 million. Clearly, this rate of liquidating endowment assets is unsustainable for the long term. The constant scarcity of funding makes it difficult for even the most basic needs to be met; according to a CCM faculty member, one teaching lab requires the use of floppy disks. Although the college administration knows and sympathizes, there is absolutely no money available to replace it.

In the CCM faculty member’s words:

“It feels like a fiefdom. Because of a drought, the serf’s land does not produce enough to pay the king. The king says ‘You owe me your tariff. Now I have to fine you.’ The serfs say, ‘But we have no money and no food.’ The king says, ‘Okay, I will feed you, but owe me both for the tariff and what I loan you to eat. You owe me no matter what the circumstances, even if there is a drought.’”

[i] Kern, Jac. (2017, September 2017), 18-23.

[ii] Spanja, S., (2015, September 2015), PBB: The High Cost of Efficiency, Works, 22.

Survey Announcement

Survey Announcement

The Collaborative on Academic Careers in Higher Education (COACHE) survey is scheduled to launch at UC the week of February 5. The survey is organized, overseen, and conducted through the Harvard Graduate School of Education (https://coache.gse.harvard.edu) which will provide aggregate data and summary analysis to UC. The goal of conducting the survey is to provide actionable data for university constituents in order to guide improvements to faculty recruitment, development, and retention. Through COACHE, the data can be compared to results from more than 250 colleges and universities.

Faculty are encouraged to participate in this anonymous Job Satisfaction Survey in order to provide the most comprehensive representation of faculty experiences at the university. The launch team has been headed by Keisha Love, Associate Provost for Faculty Development and Special Initiatives and includes AAUP and Faculty Senate representatives. Results will be available to all faculty and participation by faculty and other UC representatives will be sought to provide ideas and action steps for making improvements based on the data provided. If you have any questions, please contact Cynthia Ris, Chair of the UC Chapter AAUP’s Contract Compliance and Education Committee, at cynthia.ris@uc.edu.