Click here to read Standing Up to Attacks on Public Higher Education

Click here to read Erosion of Tenure at the University of Cincinnati 1998-99 to 2016-17 Part I

Click here to read Kiss Me, I’m Union

On February 26, arguments were made before the Supreme Court in the case Janus v AFSCME. Ostensibly this case concerns freedom of speech, but the clear goal of the groups behind this and many other cases like it is to weaken union power in our society. Billionaire-sponsored groups like the Bradley Foundation and the Koch brothers’ Americans for Prosperity are not interested in fostering individual freedom for the average hard-working person in the US. On the contrary, they are looking to damage these same individuals’ ability to protect themselves and their interests through collective action.

We need to see this case as part of a larger fight against those who want to squash not only our worker power in general but also our abilities to be effective, proper educators. The same ultra-wealthy individuals that are behind the Janus case are also advancing the increased privatization of universities, advocating for fewer restrictions of guns on campus, and directing the targeted harassment of individual university faculty members for their personal speech or academic work. Faculty at UC certainly do not share all the same values, ideas and priorities, but, as educators, we are all committed to the notion that higher educational intuitions are a positive force for our society, and that a true educational environment is one where we are free to teach, study, and research without interference from politicians or CEOs. The billionaires who have pushed cases like Janus do not share our vision of what an institution of higher education should be. For them, a university should be just another tool to advance their own interests and further entrench their own power, and us as academics are just employees expected to do the same or be removed.

It’s easy to despair when those with so much power and wealth act in such a way. But we’ve recently been provided with an amazing example in West Virginia that should give us all hope for our ability to fight back. For years, lawmakers in that state have been cutting corporate and business taxes and, subsequently, slashing funding for public schools. The state spends 11.4 percent less money per student now than it did in 2008, and its teachers are among the worst-paid in the country, ranking 48th out of 50 in average teacher salary. This year West Virginia’s educators said enough was enough. In this “right to work” state, where employees have no collective bargaining rights protected by law, teachers organized and took action. After a nine-day wildcat strike, the legislature unanimously passed a 5% raise for all teachers and school staff.

The principle of higher education as a public good, one that we all take for granted, is under threat. But the solution to this attack sits right among us. It is us. Acting in union, we can stand up to these threats to the integrity of the work that we do and to the students and communities that depend on it. As faculty, we are the most powerful force that can defend higher education from the efforts of those who sponsored the Janus case, but we can only do so if we stand together and commit energy and action to defend our values. Together, we can demand respect for academic freedom, for our meaningful participation in shared governance of the university, and for fair due process protections for all faculty.

West Virginia’s teachers have shown us the power of standing together. We can do the same. Please check today to make sure that you are a full member of our AAUP chapter.

If you aren’t sure or if you are ready to join, contact the AAAP-UC office by emailing aaupuc1@ucmail.uc.edu or calling (513) 556-6861.

Chris Campagna

Chair, AAUP-UC Associates Council

Click here to go back to the top of the page.

Erosion of Tenure at the University of Cincinnati 1998-99 to 2016-17 Part 1

Daniel Langmeyer and Dave Rubin*

Daniel Langmeyer and Dave Rubin*

For some time, the AAUP-UC Chapter has been concerned about the status of tenure at the University. Generally, comments about what was happening to tenure were anecdotal and limited to specific departments, but the overall message was that tenure and tenure track appointments were becoming less common while non-tenure track appointments were becoming more frequent. Therefore, the AAUP felt that a study addressing the matter University-wide should be undertaken, and we provide here the findings and analysis of our study.

We divided our study into two parts. The first part deals exclusively with the relative proportions of tenure/tenure track appointments and non-tenure track appointments, and their relation to student enrollments. This article reports the results of that part of the study. We also intend to do a more detailed study on the use of adjunct faculty and hope to report on that later.

DOCUMENTATION

We examined several sources of information for this article.

First, the University annually provides the AAUP with a database that includes all members of the AAUP Bargaining Unit and, among other things, includes college, department, title/rank and salaries. We used this information, by college or school, to total the number of tenure/tenure track faculty vs. non-tenure track faculty and calculate the percentage of each. By contractual definition, Faculty Members with unqualified titles are tenured/tenure track while Faculty Members with qualified titles (Adjunct, Clinical, Educator, Field Service, Research) are non-tenure track. While we had information for each year from 1998-99 through 2016-17, we summarized only every other year feeling that would be sufficient to show overall trends as well as general timelines for major changes.

Second, we have data from the Office of Institutional Research for 2008 through 2014 which provides number of faculty by college, broken among AAUP-represented and various categories of unrepresented faculty. These data provide us with information about the relative use of Bargaining Unit faculty vs. non-Bargaining Unit faculty (unrepresented adjuncts and visitors).

Third, we also obtained from the Office of Institutional Research, for Fall Semesters 2012 through 2016, percentages of total student credit hours, by college, taught by various categories of faculty.

Fourth, we obtained Fall Semester student enrollments by headcount, credit hours taken, and FTEs for each college for 2001 through 2015. These data allow us to compare trends in faculty numbers with trends in student enrollments.

RESULTS

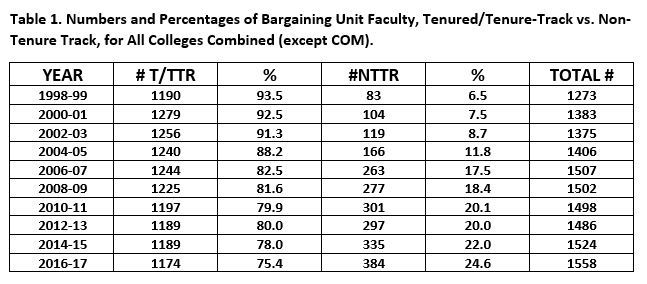

Table 1 provides a summary for all colleges combined (except the College of Medicine), in 2-year intervals beginning with 1998-99, of numbers and percentages of tenured/tenure-track Bargaining Unit faculty vs. non-tenure track Bargaining Unit faculty. The College of Medicine is not included because the clinicians in the COM were excluded from the Bargaining Unit beginning in 2007 and because the large number of clinicians would have greatly skewed the comparative percentages.

These data show a dramatic drop, from 1998-99 to 2016-17, in the percent of Bargaining Unit members that were tenured or tenure track. From 93.5% of the Bargaining Unit that was tenured/tenure track in 1998-99, that percentage fell to 75.4% in 2016-17. The decline was relatively gradual and even, except for a substantial drop of nearly 6% that occurred between 2004 and 2006, and it appears to be continuing. Actual data thus appear to substantiate the anecdotal comments that we have heard for a long time. The general erosion of tenure is clear.

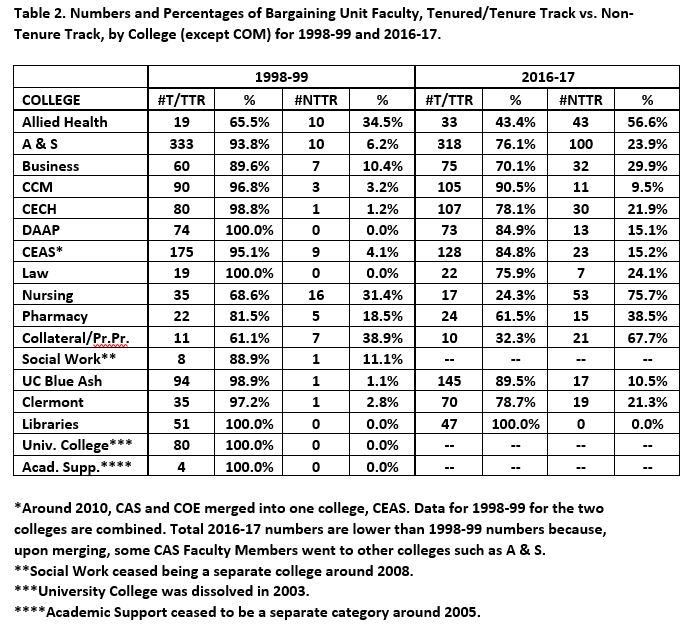

Table 2 compares the relative numbers and percentages of tenured/tenure track Bargaining Unit members vs. non-tenure track Bargaining Unit members, by college, for 1998-99 and 2016-17. These data provide a more detailed view of what has transpired during this nearly 20-year span. These data make it clear that, with exception of the University Libraries, the erosion of tenure has been University-wide and across all colleges. The extent of the erosion has varied some across colleges, with greatest changes noted for the College of Nursing where the percentage of tenured/tenure track Bargaining Unit members dropped from 68.6% to 24.3% and for Professional Practice which has seen a nearly 30% drop. For the College of Nursing, we do know that a majority of Faculty Members in 1998-99 had unqualified titles while today a majority have clinical titles. In other colleges, the numbers of tenured/tenure track Faculty Members have remained almost constant or may even have increased slightly, but there has been a much faster increase in the number of Faculty Members with qualified titles, including those with Educator titles (prior to 2010, they would have had, inappropriately, Field Service titles). At the other end of the spectrum, CCM and UC-Blue Ash continue to have approximately 90% of their Bargaining Unit faculty tenured or tenure track.

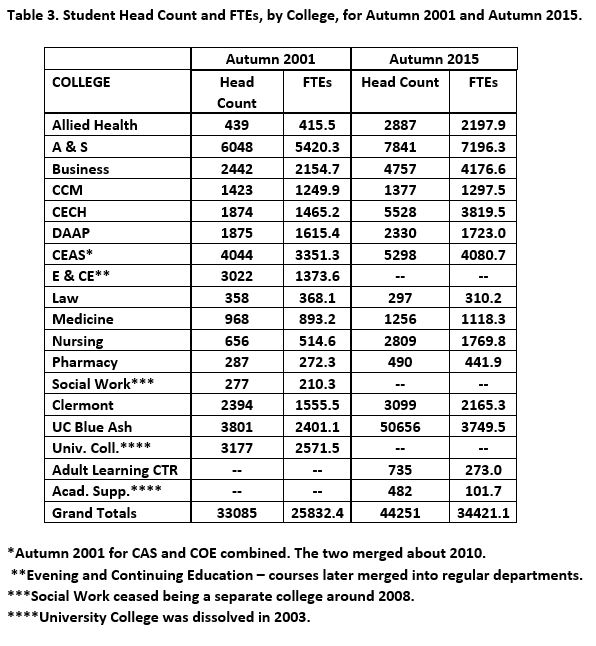

Table 3 compares student enrollment data—head count and FTEs—by college and for the total University for Autumn 2001 and Autumn 2015. During that time period, student headcount increased from 33085 to 44251, an increase of nearly 34%, and the number of student FTEs increased from 25832.4 to 34421.1, an increase of just over 33%. Over a similar time period, the numbers of tenured/tenure track Bargaining Unit members remained relatively steady—a look at those numbers in Table 1 show that number staying near 1200. In fact, that number fell from 1279 in 2000-01 to 1189 in 2014-15 at the same time that student enrollment rose by one third! Thus, the increased teaching load clearly was made up largely by increased numbers of non-tenure track Bargaining Unit members (see Table 1) and to a lesser extent by increased numbers of unrepresented faculty, also non-tenure track (see Table 4).

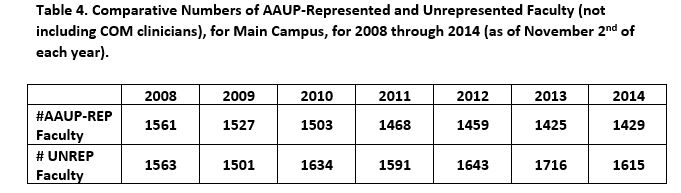

Table 4 shows numbers of AAUP-represented faculty vs. unrepresented (non-AAUP) faculty for Main Campus for 2008 through 2014. “Main Campus” excludes UC-Blue Ash and UC-Clermont. The “unrepresented” figures exclude the College of Medicine clinicians. The unrepresented faculty included in the Table were not members of the AAUP Bargaining Unit, and therefore were non-tenure track. These faculty are in addition to the non-tenure track AAUP-represented members of the AAUP Bargaining Unit as shown in Tables 1 and 2.

The numbers in Table 4 show once again the steady decline in the relative number of tenured/tenure track Faculty Members. While the numbers of unrepresented faculty fluctuate during the 7-year period charted above, the change in relative numbers of represented vs. unrepresented is clear. From almost equal numbers in 2008, in 2014 there were nearly 200 more unrepresented than AAUP-represented. When coupled with the striking reduction of tenured/tenure track among AAUP-represented faculty, the trend is clear. Proportionately more and more of the total faculty is comprised of non-tenure track individuals.

When data for individual colleges is examined, it is clear that usage of unrepresented faculty is not uniform. While the numbers of unrepresented faculty remained rather steady in some colleges, or even declined, in other colleges there were significant increases in the utilization of unrepresented faculty. Greatest increases were seen in Allied Health Sciences, Business, and Nursing. In Allied Health Sciences, usage of unrepresented faculty increased from 119 in 2008 to 150 in 2014. In Business, the increase was from 39 in 2008 to 118 in 2014. And in Nursing, there were 99 unrepresented faculty in 2008 and 219 in 2014.

Finally, from what we have already presented, it would be presumed that more and more teaching is being done by other than tenured/tenure-track faculty. As noted earlier, we examined data from Institutional Research showing student credit hours taught by various instructor types for the Autumn semesters of 2012 through 2016. Unlike the other data we examined, these data appeared to be inconsistent with regards to who was included in each faculty category, both by year and among colleges. Some numbers fluctuated dramatically during the period and were contradicted by other data that we knew to be accurate. Other numbers made no sense at all. For example, in 2012, at Blue Ash, 32% of all teaching was attributed to “Other Full-Time Faculty”, meaning that it was not done by Tenured/tenure-track, Adjunct, Clinical, Educator, Field Service, Research, Visiting or Practice faculty. What other kind of full-time faculty are there, and how could they have done 32% of the teaching? And Blue Ash was not the only college that had a high percentage of teaching done by “Other Full-Time Faculty.”

Nonetheless, some trends were apparent even in that short time period (2012–2016). During that 5-year period, the reported percentage of student credit hours taught by “Adjuncts” (we are not sure if this included, in all colleges, both represented and unrepresented adjuncts) University-wide rose from 20.8% in 2012 to 23.9% in 2016. Similarly, during the same period, the percentage of student credit hours taught by “Educator” faculty and “Field Service” faculty combined rose from 20.3% in 2012 to 26.1% in 2016. We combined these two categories because there were some title changes during that time period, from Field Service to Educator, that corrected prior misuse of the Field Service title.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

The trend over the last 15 to 20 years is clear. The UC faculty is becoming increasingly non-tenure track as a result of changes in the makeup of the AAUP Bargaining Unit and because of the increasing use of non-Bargaining Unit faculty. As a corollary, students are increasingly being taught by non-tenure track faculty.

By making these statements of fact, the authors are in no way demeaning the teaching contributions of non-tenure track faculty. Many of the latter are excellent teachers and tenure status doesn’t necessarily mean that an individual is an excellent teacher. Appointing full time faculty who are on time-limited contracts rather than granted tenure which is not so time limited allows for “flexibility,” the ability to add to or reduce the supply of instructors to meet demand within an area of teaching. Non-tenure track faculty are not expected to do as much or any research thus allowing them to focus on revenue generating activities like teaching.

But there are other things at issue. We are a Carnegie Research I institution so there must be a steady balance between the numbers of tenured/tenure-track faculty (research active) and the numbers of non-tenure track faculty (educator, non-research active). Our students deserve to be taught by faculty who are doing the most current research and can offer teaching and supervision that is the most up to date. Tenure affords a high level of protection for faculty from pressures from administrators, legislators, other faculty, or the public to censor their opinions or focus of teaching. We see that in the concerns of yet-to-be-tenured faculty who are often concerned about offending anybody and those who do not benefit from tenure who are concerned about being reappointed.

The stability of the faculty, and the security of the faculty, have a direct relation to the power of the faculty in determining University policies and University priorities. And the stability of the faculty and the security of the faculty are directly dependent upon the existence of tenure. The erosion of tenure has direct implications for loss of faculty influence and control over the educational process.

*Daniel Langmeyer is Professor Emeritus of Psychology at UC, the 2016 recipient of the AAUP-UC Chapter’s Maita Faye Levine Outstanding Service Award, and a current Chapter Trustee.

Dave Rubin is Professor Emeritus of Biology at Central State University, former Executive Director of the AAUP-UC Chapter, and a current consultant to the Chapter.

Click here to go back to the top of the page.

Kiss Me, I’m Union

On March 10th the AAUP-UC Chapter hosted a successful membership solidarity event at the Irish Heritage Center of Greater Cincinnati.

Faculty found time to discuss the progress and future plans of the AAUP, but also to celebrate with the sounds of the high-energy, traditional Irish band The Drowsy Lads.

In addition to enhancing our own connections, the Chapter contributed to the broader community by donating a portion of all tickets purchased to the East End Adult Education Center.

Thanks to all the Faculty Members who attended the event. The turnout was great and the event was a tremendous success.

Click here to go back to the top of the page.